Watch out for 'orphaned emissions' hidden in fine print: MSCI's annual sustainability trends report

Companies have tried to report lower emissions by excluding the emissions of assets or subsidiaries, or transferring them to a JV.

In 2023, much attention has been devoted to the controversy around environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing. While reports of ESG’s demise have been overstated, it is fair to say the industry is in a period of transition, says Laura Nishikawa, MSCI’s head of ESG research.

“Confusing terminology, definitions and labels have fueled challenges to ESG’s credibility from both sceptics and idealists alike. A positive outcome of the current backlash may be that years of inconsistency finally give way to greater clarity around language, goals and intentions,” says Nishikawa, a 13-year MSCI veteran who was appointed ESG research head in September.

Nishikawa fronts the 2024 edition of MSCI ESG Research’s Sustainability and Climate Trends to Watch, released on Dec 12. The annual report examines hot-button issues in the sector.

While last year’s 70-page report explored 32 topics across green bonds, nuclear energy and labour issues, this year’s edition focuses on eight topics over half as many pages.

Singapore’s coming disclosures

Singapore features in the fifth topic of this year’s report, titled “Regulation drives more corporate climate disclosures, but mind the fine print”.

MSCI’s analysts believe the next few years could see a “game-changing” volume of corporate climate disclosures becoming available to global investors. “The regulatory drive behind mandatory reporting is substantial. It covers a range of major markets, and there’s more to come. While it will no doubt place a certain burden on firms not already in the habit of this sort of measurement and disclosure, it holds out the promise of richly enhancing investors’ and financiers’ ability to make properly informed decisions and comparisons.”

But as to whether that promise becomes reality, the devil is in the details, write MSCI’s London analysts Zohir Uddin and Elchin Mammadov, along with Mathew Lee in New York and Emma Wu in Singapore.

Following the launch of the International Sustainability Standards Board’s (ISSB) disclosure standards in June, a number of jurisdictions have announced plans to implement ISSB-aligned reporting rules within their local regulatory frameworks over the coming year or so.

In the EU, companies will need to report along the lines of the European Sustainability Reporting Standards, which are designed to be interoperable with the ISSB.

Hong Kong is expected to introduce the world’s first set of ISSB-specific rules in January 2024. The UK is set to launch its own ISSB-aligned disclosure standards for registered companies by the summer of 2024, while Australia intends to finalise its ISSB-aligned reporting framework for large firms by July 2024.

Looking further down the road, ISSB-aligned disclosures are expected to become mandatory in Japan and Singapore in 2025.

However, the world’s two largest economies, the US and China, have yet to announce any formal plans to introduce ISSB-aligned reporting frameworks.

Read the fine print

As ISSB standards are gradually rolled out, investors will watch two things closely, say the MSCI analysts: the speed at which they will be able to access new disclosures and the consistency of disclosures across different regions.

Without a harmonised approach, it will be much harder to draw meaningful conclusions when comparing performance globally, they add.

With rising costs, companies may be tempted to slow down plans to decarbonise, but walking back climate promises can draw criticism.

MSCI warns of “footnotes and exceptions” in climate reporting that allow companies to stay committed to certain fossil-fuel assets without counting their emissions in their headline numbers.

“Going into 2024, it may be increasingly important to read the fine print to sort the active transition plans from the differences in accounting.”

MSCI has seen companies employ several methods to reduce their reported emissions, such as excluding the emissions of assets or subsidiaries that are not wholly operated by the company.

Joint ventures (JVs) are relatively common in energy exploration, they note, and some corporates deconsolidate the emissions of pollutive assets after transferring them into a new JV or spinoff, while continuing to incorporate their share of net income.

Some have tried excluding emissions from business units that are planned for sale, while others have switched from location-based to market-based emissions accounting.

MSCI has also seen companies structuring finance as corporate debt issued by a special-purpose vehicle with a lower reported emissions footprint, rather than linked to specific fossil-fuel projects.

“Our research on four publicly-traded utilities that had omitted some direct emissions from their reporting by attributing them to a combination of JVs, subsidiaries and investments, and/or switching to market-based emissions accounting, found they were excluding 17%-95% of what their overall emissions footprint could be,” says MSCI.

“Although these grey areas in emissions reporting practices may ultimately be clarified by regulations, in the interim, investors may need to be wary of ‘orphaned emissions’.”

Who’s minding the shop?

Another topic in this year’s report examines the growing scope of corporate oversight. “One of the most dramatic changes we’ve observed over the last year has been in the behaviour of audit regulators, which is sparking fresh attention to audit practices, board oversight and the quality of auditors themselves,” writes a team of MSCI analysts from New York, Toronto, Tokyo and Frankfurt.

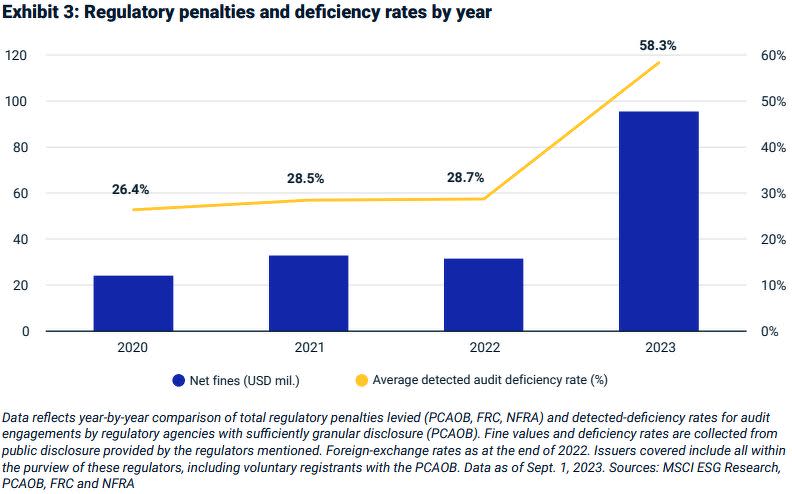

Across multiple markets, regulators spotted far more audit deficiencies and levied more financial penalties in 2023 than previous years, according to MSCI.

As of September, financial penalties across three major regulators — the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) in the US, Financial Reporting Council (FRC) in the UK and National Financial Reporting Authority (NFRA) in India — were up 302%, compared with 2022.

In the US, detected deficiencies in audit engagements spiked 203% over the same period.

Investors should look at the audit and risk-oversight capabilities of the boards of companies in their portfolios, says MSCI. “The potential consequences of weak oversight were highlighted by 2023’s US banking crisis and the failure of Credit Suisse. We found that almost a quarter (24%) of the global banks we analysed had been working with the same auditor for more than two decades, which may compromise independence.”

MSCI’s analysis of 460 banking constituents of the MSCI ACWI Investable Market Index found that 42% lacked an industry expert on their audit committee, and a majority (54%) had no risk management expert on the board.

Boards choosing tech, cybersecurity skills over financial, risk expertise

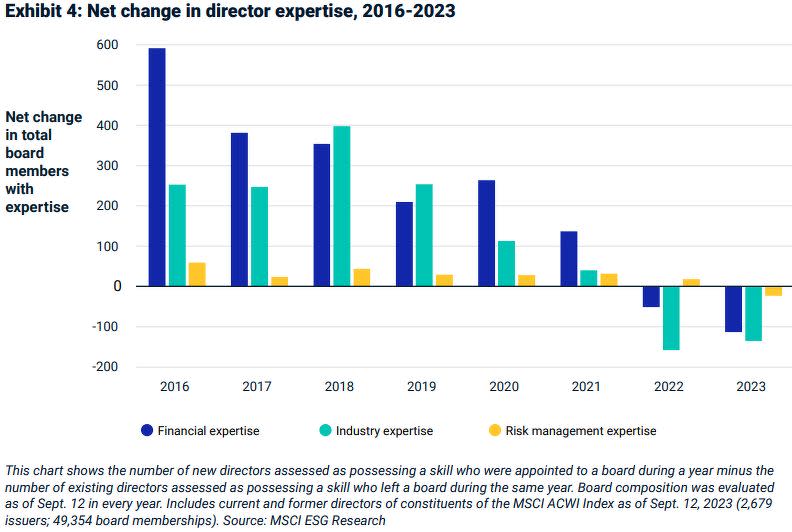

In 2023, constituents of the MSCI ACWI Index saw an overall decrease in the number of board seats held by people who possess three core competencies: financial expertise, risk management expertise and industry expertise.

The prior year saw a deficit in two of these three skills, despite the average size of boards increasing in 2022 and holding steady in 2023, says MSCI. These recent declines contrast with a net increase between 2016 and 2021.

Nominating committees appear to be prioritising new skills. MSCI used generative AI to read the biographies of directors first elected in 2022 and 2023 and assign skills to each. “Fittingly, technology and cybersecurity were the most commonly identified areas of expertise after general management experience. Other top skillsets included engineering, ESG/sustainability and manufacturing/logistics.”

MSCI also observed that female directors, directors with risk management expertise and those with financial expertise tend to sit on more boards than average. “This was more pronounced among non-executive directors, raising concern over time commitments for those directors who are most crucial to the independent oversight of management.”

Infographics: MSCI

See Also:

Click here to stay updated with the Latest Business & Investment News in Singapore

MSCI's new Sustainability Institute aims to create real-world influence and action

TNFD framework launch floats nature-related risks to corporates' attention

Get in-depth insights from our expert contributors, and dive into financial and economic trends

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance