The ultra-rich are trading their wealth for health with expensive, experimental treatments — but can the ‘largely unregulated’ longevity industry really help you turn back time?

The only thing money can’t buy is time — but America’s ultra-wealthy are now doing their best to change that, putting their dollars into research and expensive treatments to slow down, or even backpedal, their aging process.

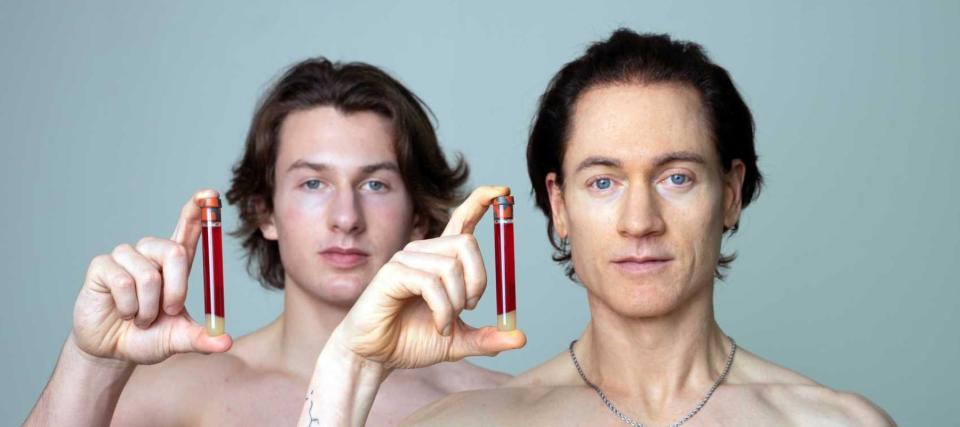

Just look at tech millionaire Bryan Johnson, the 46-year-old spending about $2 million a year in his quest to turn back time.

Don’t miss

Commercial real estate has outperformed the S&P 500 over 25 years. Here's how to diversify your portfolio without the headache of being a landlord

Take control of your finances in 2024: 5 money moves to start the new year off strong

The US dollar has lost 87% of its purchasing power since 1971 — invest in this stable asset before you lose your retirement fund

Johnson’s regime includes ingesting dozens of supplements, a vegan diet and injectable gene therapy — and he once notoriously received a blood plasma transfusion from his teenage son (which he later admitted didn’t work).

While some clinics and practitioners offer experimental treatments, others claim their methods are science-based and proven to be effective. Access to quality, however, often comes at a price.

And, as Matt Fellowes, an advisory council member at the Stanford Center on Longevity and co-founder of health insights platform, BellSant, points out, that’s created a massive opportunity for predatory and scammy products.

“The reality is that our health system is designed to keep people alive, not to keep them healthy,” Fellowes told Moneywise in an email. “And, in the absence of those professionals focused on health, a $400 billion wellness economy has emerged, which is largely unregulated and often full of products that don’t work.”

Interest in the longevity space has been growing

The COVID-19 pandemic might have helped spark increased interest in the wellness sphere, but humans have always been intrigued by the prospect of lengthening their lives.

But as scientific and technological advances have led to Americans living increasingly longer lives, they’re also experiencing higher rates of chronic illness, such as asthma, hypertension and diabetes.

In the meantime, Fellowes says, a group of super-wealthy individuals interested in extending their lives and promoting healthy aging has emerged. And, in turn, this group of elites is driving more media coverage, research and interest in longevity medicine.

“Even though there’s still evidence needed to validate a lot of [longevity medicine], affluent people have the luxury of trying a lot of it out to see what works,” he explains.

There are no official counts of longevity clinics in the U.S., but industry estimates range between 50 to 800, according to The Wall Street Journal. The publication reports that an analysis from longevity research and media company Longevity.Technology also found that venture-capital investment in clinics more than doubled between 2021 and 2022, from $27 million to $57 million across the globe.

But drinking from the fountain of youth comes with a hefty price tag. Many clinics that are science-based and include a team of internists — doctors who specialize in internal medicine — and specialists like cardiologists, dermatologists and dieticians, and even geneticists and epidemiologists, are more likely to come with higher costs and are targeted toward higher-income households, says Fellowes.

And clinic entrance fees can stretch to $100,000 a year in the U.S., where many of these services don’t get covered by the standard health insurance policy.

Read more: Find out how to save up to $820 annually on car insurance and get the best rates possible

How do you measure the benefits of longevity medicine?

But it’s not just the ultra-wealthy who are interested in lengthening or improving the quality of their lives. Dr. Andrea Maier, a professor in medicine and healthy aging and co-director for the Centre for Healthy Longevity in Singapore, works with patients of all ages and income brackets.

Maier has her own private longevity clinic, but also works at a longevity clinic at a publicly funded hospital, where patients can get some of their treatments covered by health insurance.

However, the majority of her clients are 45- to 65-year-olds who are concerned about developing age-related diseases and have the disposable income to invest in themselves.

Evidence-based clinics like Maier’s might examine your “biomarkers” — which can age you differently than your chronological age — through procedures like blood tests, cognitive tasks or physical performance.

Treatments can go beyond recommending certain supplements or diet and lifestyle changes, like skipping sugar in your coffee and not smoking — they need to be specifically tailored to the patient’s biology and needs.

While she says it’s possible to reverse your biological age by as much as 20 years, turning back the clock three to five years is often more realistic for patients who don’t want to completely change their lives. Maier says her patients often see results within four to six months but as humans are constantly aging, to keep those results, patients must maintain their lifestyle changes.

However, Maier says another important metric to consider is how you’re contributing to society (before and after receiving treatments), such as your productivity at work, and your emotional wellness, through your relationships or outlook on life.

The issue with longevity clinics

Accessibility is one thing, but there's also the question of the safety and efficacy of longevity products.

“The difficulty is that our field is not regulated at this moment in time,” Maier admits. “Every physician can say, ‘I [practice] health longevity,’ but it doesn't mean that you get the quality.”

Maier helps manage the Healthy Longevity Medicine Society, an international organization established in 2022, which is working to set and promote professional standards around longevity medicine and promote accreditations and credentials for practitioners.

She believes greater demand and research will make treatments more cost-effective and accessible to the general public. She compares longevity clinics to cellphones, which were initially considered luxury items but have now become commonplace across income groups around the world.

Of course, we’re still a long way from longevity treatments becoming as ubiquitous as cellphones. Just like with other conventional medicines and treatments in development, Maier says longevity treatments need to undergo trials in controlled environments to determine what works and can be invested in.

But she notes there are some clinics, and patients like Johnson for example, who may be willing to try experimental procedures to reverse their biological age.

Maier emphasizes that when it comes to their bodies, it’s crucial that clients do their research and compare what different clinics offer.

“If somebody says, with one drip, you're going to be 10 years younger and you’ll feel beautiful, very often this might not be the case, because changing the biology takes time,” she warns.

What to read next

This Pennsylvania trio bought a $100K abandoned school and turned it into a 31-unit apartment building — how to invest in real estate without all the heavy lifting

Jeff Bezos and Oprah Winfrey invest in this asset to keep their wealth safe — you may want to do the same in 2024

Rising prices are throwing off Americans' retirement plans — here’s how to get your savings back on track

This article provides information only and should not be construed as advice. It is provided without warranty of any kind.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance