Housing insurance is melting down in several property markets as climate change renders old assumptions obsolete

The end of climate stability signals the end of the insurance market as we know it. Will it also signal the beginning of a broader understanding of physical risks by equity and debt holders, regulators, and citizens? The answer to that question will determine whether climate risk changes capital markets forever. Put succinctly: The first time a property floods, it’s an insurance problem, and maybe the second time, but after that, it’s an equity and debt problem.

It's important to understand that insurance isn’t protection against hazards like flooding, wind, fire, or hail. It’s a financial contract to reimburse property owners for the cost of repairing structures only after events that are predictably rare. If hazards stop being rare, stop being predictable, and/or produce damages that aren’t easily reparable (or suggest that a building should not be rebuilt in that location), the existing market structures for both property insurance and property more broadly won’t work.

Climate stability underpins a myriad of assumptions. Farmers could plant the same crops decade after decade. Architects, builders, engineers, and city planners could follow building codes and engineering standards based on past ranges of temperature and rainfall without learning about local climates. Real estate became an asset class valued on spreadsheets and two-dimensional databases. The weather was so well-behaved that only a few specialists concerned themselves with it.

Past patterns and ranges of weather that repeated over time enabled a huge, reliable property insurance market that relieved asset owners and lenders of estimating and preparing for events with low probabilities. Not only could specialists assess which events had a 1% probability in a given year (“1-in-100 year events”), they could anticipate the damage those events would cause.

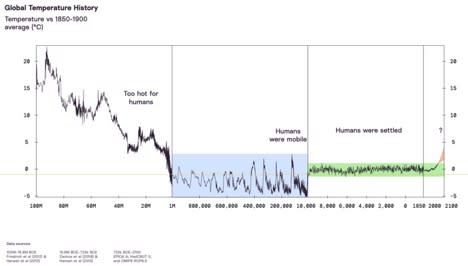

Unfortunately, historical weather data is no longer a good guide even to our present, let alone the future. The atmosphere is warmer than it has been since the dawn of civilization and is continuing to warm. Here is a graph of average atmospheric temperature going back 100 million years. The green band shows the narrow range that enabled civilization.

Today’s insurance markets are full of quirks that derive from assumed stability:

Virtually all property insurance is annual. There is no term structure.

After a claim, the insured is expected to rebuild the same building in the same place.

Insurance is only available for damages to a structure, not to the value of the land.

Regulators often insist on the use of backward-looking data, prohibiting the use of climate models and climate-aware catastrophe models.

Regulators also regularly limit the amount by which insurance rates can rise year-to-year.

Climate change undermines all of these assumptions.

Investors largely (and logically) assume that insurance markets are pricing physical risks, so pension funds, investment managers, banks, and even real estate companies have historically not researched climate risk. For example, mortgage loans often require borrowers to have insurance, yet a 30-year loan doesn’t need to be matched with a 30-year insurance policy: A one-year policy is treated as a sufficient signal that insurance will be available at roughly the same cost over the duration of the loan.

A few years ago, sophisticated users of climate and weather models (notably, reinsurers and insurance-linked investment funds) began withdrawing from some markets. Their retreat left insurers unable to off-load tail risks just as the tails were getting bigger. In turn, insurers–most of whom are prohibited by regulators from rapidly increasing rates–have begun to retreat from markets, especially in Florida and California. In response, governments have stepped in to provide coverage.

Government insurance plans were set up decades ago in nearly every coastal state to bolster property markets during periods of market dislocation. Such interventions were intended to be temporary, as risks would–naturally–return to their historical ranges and market dislocations would end. Unfortunately, the insurance markets are unlikely to view the current dislocation as temporary, and will not “come back” to bail out governments that are implicitly assuring their residents that they are entitled to affordable insurance no matter what. Without explicitly saying so–and without citizens voting–governments are turning property insurance from a financial product priced by markets into an implicit right. This quiet transfer of risk should worry everyone.

Reassessing the assumptions on which we built society will be challenging, but climate science can help us figure out how to live well in a warmer world. The same models that accurately anticipated rising heat and humidity, increased drought and deluge, rising oceans, bigger tropical storms, elevated wildfire risk, and weakening jet streams warned sophisticated investors away from insuring the fattening tails. The same research and data can help decision-makers of all kinds integrate this information into processes as diverse as city planning, building codes, mortgage underwriting (including by FNME and FMCC), and REIT valuation. Free educational, mapping, and risk tools such as those offered by Probable Futures, Climate Central, and FirstStreet are good places to start.

Almost 12,000 years ago, our hunting and gathering ancestors noticed that the climate had stopped changing. In response, they stopped wandering, settled in communities, and began developing the complex, specialized civilization we have today. If we keep assuming that risk is only the responsibility of insurance markets, the strains of increasing heat, drought, storms, etc. will be compounded by increasingly dysfunctional markets and ballooning government balance sheets.

Thankfully, unlike our ancestors, we not only know why the climate is changing but can also anticipate where and how much. If we become climate literate, society can begin assessing current and future risks and figure out how to make sure financial markets reflect them.

More must-read commentary published by Fortune:

Booz Allen Hamilton CEO: America needs a whole-of-nation approach in its great power competition with China

‘A head-in-the-sand approach’: The U.S. strategic drug stockpile is inadequate for a bird flu outbreak

The national debt is over $34 trillion. It’s time to tell the truth about the U.S. government’s finances

‘Sometimes, the facts don’t matter’: Attacks on DEI are an anti-capitalist war on American prosperity

The opinions expressed in Fortune.com commentary pieces are solely the views of their authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of Fortune.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance