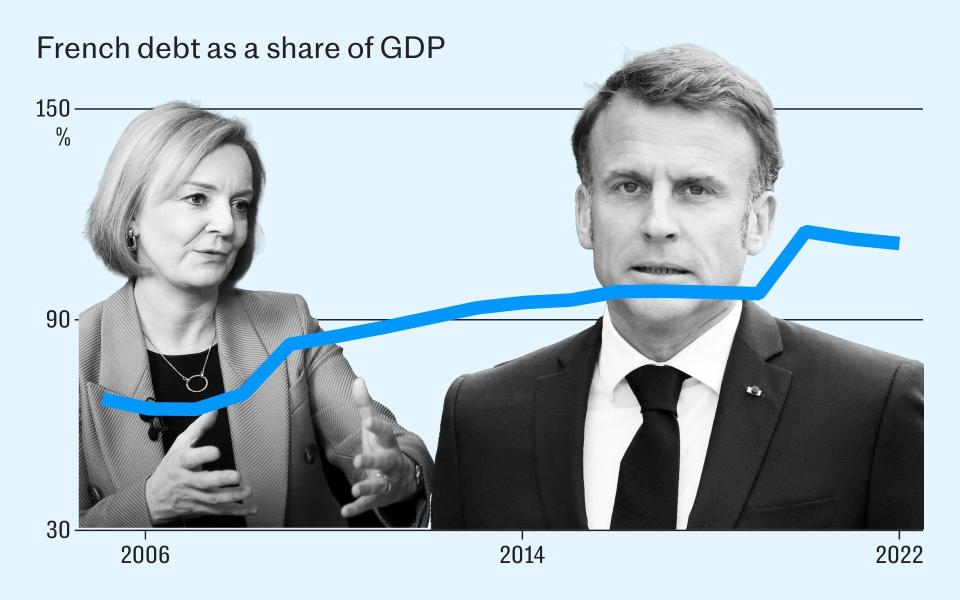

How French extravagance made Macron the new Liz Truss

Liz Truss has emerged as the unlikely bogeyman hanging over France’s economy.

In an attempt to deter voters from siding with Marine Le Pen’s National Rally party, rivals have invoked the former UK prime minister to sound the alarm over the consequences of low taxes and high spending.

Bruno Le Maire, France’s economy minister, went as far as to say that the country risks a debt crisis if Le Pen succeeds at the polls.

“A Liz Truss-style scenario is possible,” he said last week.

Such grave warnings have raised fears across Europe’s financial markets, fuelling a recent surge in French borrowing costs.

Historically, lenders have been happy for the French government to borrow at interest rates similar to that of other strong economies, such as Germany.

However, they are now charging a rate much closer to that of Portugal, which has traditionally been viewed as a riskier bet.

Unfortunately for Le Maire, as well as other critics of Le Pen, many are quick to highlight that Emmanuel Macron’s government has left France vulnerable through years of heavy borrowing.

This has coincided with a consistent uptick in French borrowing costs, which have been rising relative to Germany’s for some time.

Markets have responded accordingly by charging higher rates on France’s debt – as was the case during Truss’s short-lived premiership.

A decade ago, France’s borrowing costs were between 0.2 and 0.4 percentage points higher than Germany’s, whereas that has now jumped to 0.8.

While Covid and the energy crisis fuelled the need for greater spending, Macron has been slow to return the country’s finances to a steady footing.

That is without taking into account that recent fears of a debt crisis were only sparked after Macron announced snap elections earlier this month.

Unsurprisingly, Le Pen has spearheaded these attacks.

“The chaos is him,” she told the French newspaper Le Figaro.

“Social chaos, chaos on security issues, chaos with migration and now institutional chaos.”

Fears Le Pen will increase debt pile

Recent concerns around a prospective Le Pen government have centred on how her efforts to cut taxes and increase spending will only increase the country’s debt pile further.

However, fears across trading floors have been linked to how Macron racked up debts over the past seven years, leaving bond markets on a hair trigger for any further shocks.

The long rise in French debt levels can be traced back to the financial crisis.

Before the credit crunch, the country’s national debt amounted to around two thirds of GDP – much like Germany’s. By 2010, both were above 80pc.

Since then, Germany has successfully regained control of its finances and brought debt levels back down to around 66pc, even while tackling Covid and the energy crisis.

By contrast, France has kept borrowing.

According to the International Monetary Fund’s measure, its national debt reached more than 97pc of GDP before the pandemic – and is now beyond 110pc.

Mohit Kumar, chief economist for Europe at Jefferies, says French political culture has made it hard for any government to rein in borrowing.

He says: “It is unpopular and it is difficult because you have to go through a fiscal consolidation, which is never popular.

“It is more difficult in France compared with Germany. Germany has always been about fiscal prudence, and I think the voters are very much in favour of fiscal prudence.”

Despite such concerns, Macron has vowed to keep on borrowing.

Under current plans laid out before the election, the IMF predicted its deficit will remain high, declining from 5.3pc of GDP this year to 4.5pc by 2027.

This is well above the EU’s goal of keeping annual borrowing below 3pc and was published before Macron announced the snap election – which has raised the likelihood of a more profligate party taking over.

Jim Leaviss, chief investment officer of public fixed income at M&G, says it has markets worried.

“There was already some nervousness around French borrowing,” he says.

“Then we have the snap parliamentary elections called, which raised the prospects of Macron losing control of the parliament, probably to the Right.

“Whoever wins, whether Right or Left, both manifestos imply higher degrees of government spending.”

Macron’s pension reforms, which raised the state retirement age from 62 to 64, have proven to be particularly unpopular among voters.

Yet reversing those would represent a critical step away from fiscal prudence and sour confidence among investors, economists have said.

“Whoever wins, it looks like the answer is more spending, from a government where people are already a bit nervous about the deterioration in finances,” Leaviss says.

‘Too big to fail’

Erik-Jan van Harn, at Rabobank, says France once had a special status as a founding member of the EU, describing the country’s economy as “too big to fail”.

However, he says the scale of its debts combined with the prospect of a less EU-friendly government under Le Pen has changed that.

This has led to the return of bond vigilantes – traders keen to enforce financial discipline by driving up borrowing costs of profligate states.

“It really matters because debt sustainability, which is what bond vigilantes are all about, gets a more important position now,” Van Harn says.

“There has been a shift to putting more weight on the fundamentals of the country now that it does not have this special position, or it is not as pronounced as a couple of years ago.”

This is critical because a country’s economy must be deemed responsible in the event of financial emergencies.

In the Truss era, the Bank of England stepped in to calm markets once a cycle of falling bond prices sparked a spiral of selling.

However, so far, the European Central Bank (ECB) has been keen to stress it has no plans to do the same in France.

Philip Lane, the chief economist at the ECB, recently played down the threat of instability and said bond turbulence did not merit intervention.

Speaking at a Reuters event at the London Stock Exchange on Monday, he said: “What we’re seeing in the markets is repricing. But it’s not in the world of disorderly market dynamics as of now.”

However, he accepted there is “inherently more fragility in the European financial system” because the monetary union is made up of 20 sovereign markets.

As a result, he said: “It is very important the ECB makes clear that we will not tolerate unwarranted and disorderly market dynamics that would pose a series of traps to the transmission of monetary policy.”

He added: “We cannot have a case where essentially market panic, market illiquidity, market sentiment disrupts our monetary policy.”

All of this indicates that while France may not be at crisis levels just yet, the ECB is sharpening its tools should a full-blown debt panic break loose.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance