What Exxon and Elon tell us about the ‘myth of the shareholder franchise’

Wherever you stand on the shareholder vs. stakeholder capitalism debate, there is one thing everyone can probably agree on: The idea that corporate America is built on shareholder primacy is largely a myth. The most powerful stakeholder in many U.S. listed companies is the CEO and chairman, followed by the board, and their interests often trump those of others when conflicts arise.

Two events from the past week underline this point, which has been argued by legal scholars on all sides of the ideological spectrum since the 1930s until the present day.

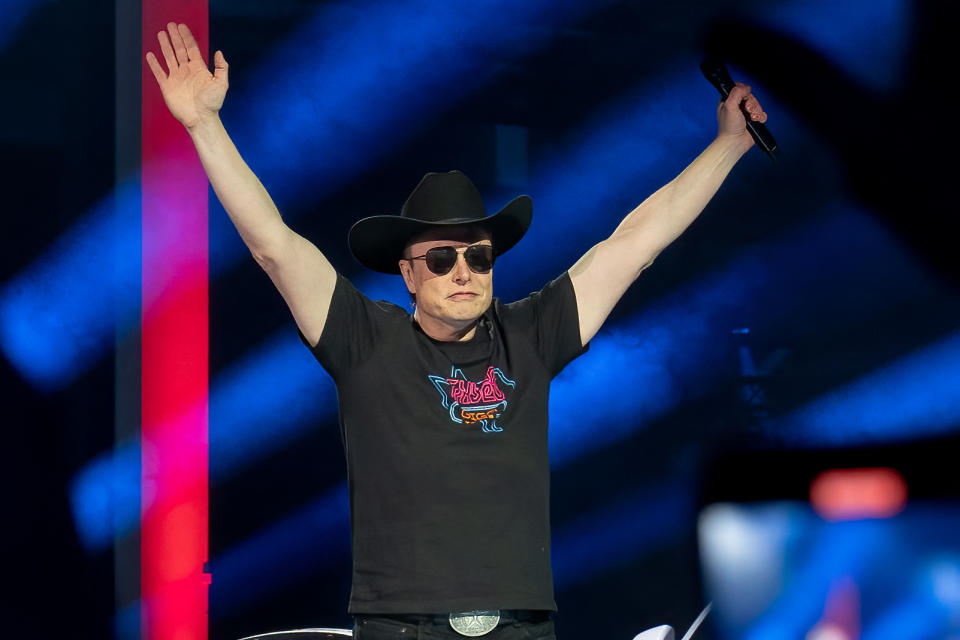

The first is that CEO Elon Musk threatened to move the Tesla headquarters from Delaware to Texas, following a judge's decision to void his $56 billion pay package. The second is that Exxon continues to sue one of its activist shareholders for repeatedly pushing for a proxy vote on its carbon emissions reduction plan, even after the shareholder in question backed out of his proposal.

Let’s briefly look at the two cases. In the case of Tesla, a Delaware judge last week ruled that the Tesla board did not properly do its job in protecting shareholder interests in 2020 when it approved a pay package for CEO Elon Musk that could grant him up to $56 billion in shares and other compensation over the years of his contract. (For comparison, the median annual compensation for CEOs of America’s largest companies is $14.8 million a year, a figure already widely viewed as bloated compared with staff compensation.)

The decision rested not on the size of the pay package per se, but rather on the fact that no serious efforts were undertaken to ensure that the pay package was in the best interest of shareholders.

Then there's the case of Exxon, which decided to continue to sue one of its activist shareholders, the Dutch group Follow This, for their repeated efforts to have shareholders vote on climate proposals. To sue the group is one thing; more remarkable is that the case wasn’t dropped even after Follow This withdrew its proxy vote proposal.

For observers, it was a clear sign that Exxon management wanted to set an example. “Part of the goal here of [Exxon] is to make it prohibitively costly, for particularly smaller investors to make their voices heard,” Josh Zinner, chief executive of the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility, told the Financial Times this week.

These two cases are stark reminders of the relativity of shareholder power in American companies, compared to the implicit power that resides with top management and boards. And that is not new: Nearly 100 years ago, Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means first observed that shareholders are “subservient” to directors “who can employ the proxy machinery to become a self-perpetuating body.”

The person who resuscitated this 100-year-old observation in recent years was the late Lynn Stout, a scholar who argued for stakeholder capitalism. But even the scholars who advocate for shareholder primacy, such as Harvard professor Lucian Bebchuk, agree with this observation. “The power of shareholders to replace the board is a central element in the accepted theory of the modern public corporation with dispersed ownership,” he wrote a decade ago. “This power, however, is largely a myth.”

The cases of Exxon and Tesla today show that these observations still very much hold true. It means that whether you believe companies should be run in the interests of shareholders, or a broader set of stakeholders, the one common action point anyone should get behind is this: The CEO and chairman and other directors should have guardrails in place to guarantee they act in the interest of the company and its shareholders.

More news below.

Peter Vanham

Executive Editor, Fortune

peter.vanham@fortune.com

This edition of Impact Report was edited by Holly Ojalvo.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance