Even Jerome Powell is having trouble reading this economy

'By the way, I’m not blessing any particular level of longer-term rates'

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell just delivered his final remarks before the central bank’s next policy decision, the highlight of a busy month of central banker speeches before their blackout period begins. The public appearances have cemented the perception that the Fed will hold rates steady at its next meeting and probably through the end of the year.

As for next year, however, even Powell, the most powerful man in global finance, can’t pretend to know what’s in store. Here’s how he put it on Thursday in his prepared remarks at the Economic Club of New York, which were later followed by an on-stage interview with Bloomberg’s David Westin:

A range of uncertainties, both old and new, complicate our task of balancing the risk of tightening monetary policy too much against the risk of tightening too little. Doing too little could allow above-target inflation to become entrenched and ultimately require monetary policy to wring more persistent inflation from the economy at a high cost to employment. Doing too much could also do unnecessary harm to the economy.

Given the uncertainties and risks, and how far we have come, the Committee is proceeding carefully. We will make decisions about the extent of additional policy firming and how long policy will remain restrictive based on the totality of the incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks.

In short, the longer-term path ahead is anyone’s guess. All we can do is focus on the near and present, so let’s start by doing just that.

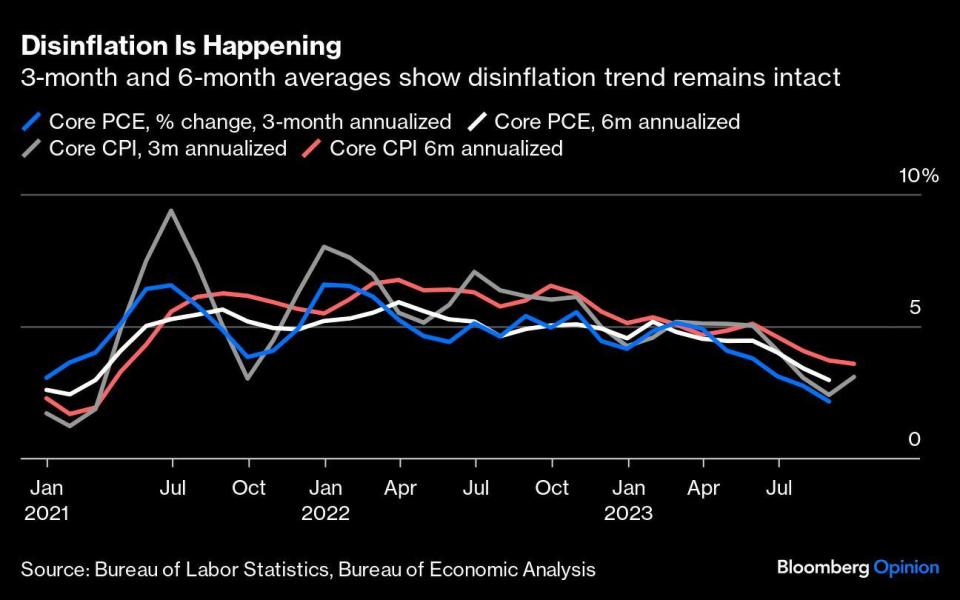

At the time of writing, Fed funds futures imply just 2% odds of a Fed rate increase next month and about one-in-four odds of a hike at the year’s last meeting in December. Over the course of the past month, few policymakers have explicitly endorsed an imminent need for further rate increases. Working in favor of the doves was a string of relatively benign inflation data. On a three-month and six-month annualized basis, core personal consumption expenditures inflation — the Fed’s preferred gauge — is running at just about 2.2% and 3%, respectively — essentially within spitting distance of the Fed’s 2% target.

What would it take for officials to confidently arrive at the conclusion that a reacceleration is afoot? Inflation data can be erratic from month to month, and it’s subject to revisions. As a consequence, you’d need essentially all of the forthcoming inflation data published before the year’s final decision (two CPI and PCE reports) to be quite bad to meaningfully shift the six-month moving averages. To get the 6-month trendline moving up again on core PCE, you’d need, for example, at least one 0.4% month-on-month increase. Could it happen? Sure, but the short calendar alone suggests it’s unlikely to transpire before the end of the year.

Next year, however, is another story, as policymakers will have hard data by then on a number of emerging risks to the outlook. First, they’ll get more information on the strength in the real economy. The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow tracking estimate puts annualized third-quarter growth at a remarkable 5.4%, a pace that’s more than twice most estimates of the economy’s non-inflationary speed limit — which economists refer to as its potential growth rate. Economic orthodoxy would suggest that this trend in inconsistent with continuing disinflation, and Chair Powell seems to place some stock in that view. Here’s how he put it on Thursday:

We are attentive to recent data showing the resilience of economic growth and demand for labor. Additional evidence of persistently above-trend growth, or that tightness in the labor market is no longer easing, could put further progress on inflation at risk and could warrant further tightening of monetary policy.

But in this unusual post-pandemic economy, policymakers will want to wait for empirical evidence about what’s really happening: is the economic strength durable, or will tighter borrowing costs start to bite any time now? And how does that strength feed though into prices, if at all? As Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago President Austan Goolsbee said in a speech late last month, this isn’t a typical economy and it may not proceed in accordance with economic orthodoxy. Here’s Goolsbee:

"...another answer is that something very different is going on: Either nonmonetary shocks are heavily influencing the economy or the nature of the monetary policy environment we are working in today is different. I believe both of these factors are at play. If so, we need to be extra careful about indexing policy to this traditional view of what the incoming data on output and the labor market mean for the inflation outlook.

Second, another several months should give policymakers an opportunity to assess the economic fallout from the tragic developments in Israel. An escalation in the conflict that spreads through the region would likely drive prices for oil and other commodities higher. Even then, the devil will be in the details. Policymakers must be cognizant of any impact on consumer inflation expectations, which — subdued as they’ve been — could drift higher on the back of another round of price shocks at the gas pump, though some may be inclined to “look through” volatile energy prices that are set on global markets.

Finally, the additional months of “wait and see” monetary policy should allow Fed voters to assess the impact of rising longer-term bond yields and their knock-on effects on higher mortgage, auto and business loan rates. The conventional wisdom here is that the jump in Treasury yields is doing some of the Fed’s work for it, tightening financial conditions for consumers and businesses without the Fed needing to officially change anything in their stance. Powell generally agrees, but he doesn’t want to assume anything. Here is Powell responding to a question from Bloomberg’s Westin on the impact of surging bond yields.

WESTIN: It seems like almost arithmetic, it must reduce some of the impetus for you to continue to raise rates.

POWELL: At the margin it could. I mean I think that remains to be seen. And by the way, I’m not blessing any particular level of longer-term rates. But just in principle, that’s right.

Putting the pieces together, it’s relatively clear that there are still a number of paths to potentially higher policy rates in 2024, and it’s hard to make any high-conviction bets in one direction or the other. Strong growth and rebounding energy prices could force the Fed to do more, but durably higher bond yields could also serve as a mitigating force, and the margin of uncertainty around all of those variables is extraordinarily high. That’s why I’m inherently skeptical anytime someone makes a bold forecast about this economy. Even Powell — one of the few people in the world with the power to directly influence the future of the entire financial system — has no idea what comes next. - Bloomberg Opinion

See Also:

Click here to stay updated with the Latest Business & Investment News in Singapore

Powell signals Fed to stay on hold and keep future hike on table

Fed officials prepare to extend rate pause without saying hikes are done

Get in-depth insights from our expert contributors, and dive into financial and economic trends

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance