How Boeing broke down: Inside the series of leadership failures that hobbled the airline giant

It was the blowout heard round the world.

It was Jan. 5, just after Alaska Airlines Flight 1282 had taken off from Portland, Ore., en route to Ontario, Calif., when a two-by-four-foot panel blew out at three miles high, leaving a gaping hole in the side of the Boeing 737-9 Max. “There was the loudest explosion,” recalled passenger Joan Marin. “The wind, the noise, the roar.” Terrified passengers grabbed for falling oxygen masks. The intense vacuum ripped the V-neck sweater and T-shirt from a 15-year-old in a window seat at the edge of the void, and sent his headset and cell phone flying into the evening sky.

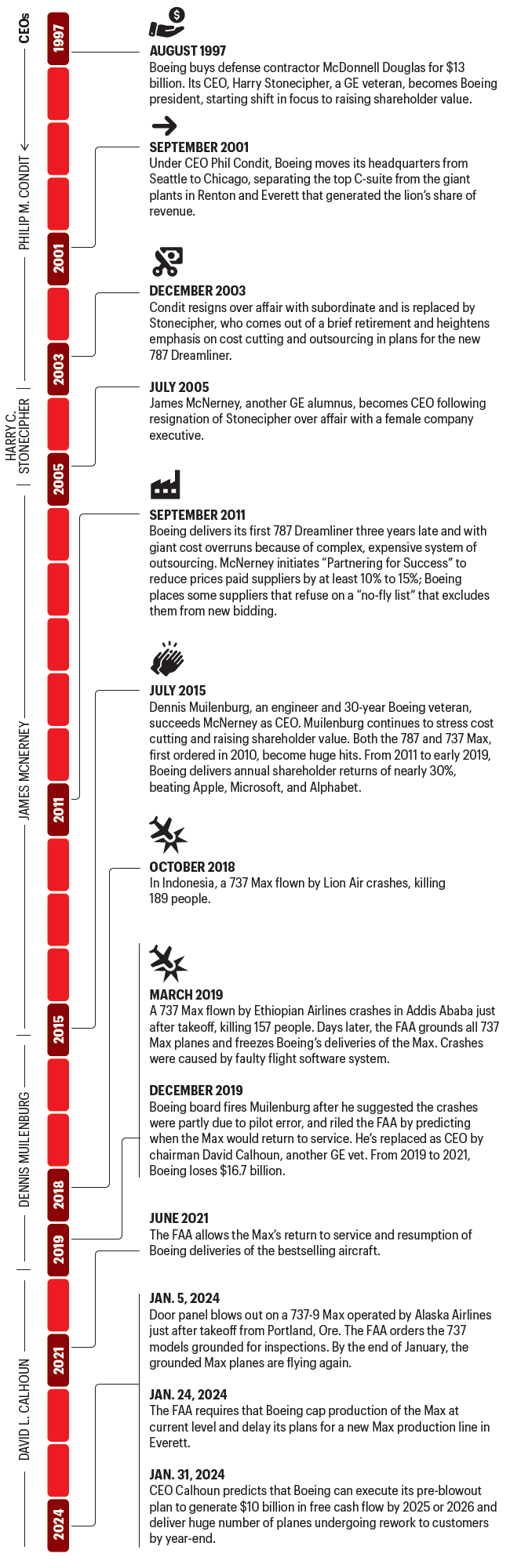

For Boeing, the company that built the plane, it was a crushing blow. The 108-year-old corporate icon had been dogged by safety concerns since two fatal crashes darkened its reputation and sent its finances reeling a half-decade ago—the Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines disasters that together killed 346 people. The response to those catastrophes got then-CEO Dennis Muilenburg fired, and current CEO David Calhoun, a 26-year GE veteran, took the helm in January of 2020. Professed Calhoun following the door blowout: “We’re going to approach this, number one, by acknowledging our mistake. We’re going to approach it with 100% and complete transparency every step of the way.” The disaster's jet stream claimed the 737's program's production chief, whom Boeing ousted on February 21.

Customers were not appeased. In a CNBC interview on Jan. 23, outspoken United Airlines CEO Scott Kirby declared that the Alaska Airlines accident will significantly set back the timeline for approval of the 737-10, which Kirby had previously chosen as a principal aircraft in United’s ambitious blueprint for expansion. He isn’t saying that United will cancel its standing orders. But he strongly suggests that his airline is no longer making the 737-10 the main vehicle for the liftoff to come. “We’re going to at least build a plan that doesn’t have the Max 10 in it,” said Kirby. “The Max 9 grounding is probably the straw that broke the camel’s back for us.”

As customers fumed, Boeing’s principal regulator imposed tough new restrictions that will greatly limit the planemaker’s freedom of action. On Jan. 24, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) took the extraordinary measure of capping the output for the entire Max lineup now in commercial production, consisting of the 737-8 and 737-9, at the current rate of 38 per month. That’s a serious blow, since Boeing was basing its comeback campaign on gradually raising its monthly Max output to 50 by 2025 or 2026. As part of its expansion blueprint, Boeing had planned to open a new production line at its facility in Everett, Wash., for the Max, north of the plant in Renton, where it makes all its 737s today. But the Portland catastrophe prompted the FAA to withhold approval for now on the Everett addition, until Boeing shows the progress required by the FAA. In a press release, FAA Administrator Mike Whitaker declared: “This won’t be back to business as usual for Boeing.”

Boeing’s trajectory from here towers as one of the most significant business dramas of this millennium. U.S. airlines carried over 900 million passengers in 2023, over one-quarter more than in 2013 and roughly matching pre-pandemic numbers. Boeing produced around 40% of the 29,000 commercial aircraft filling the skies worldwide. This is the company that launched the jet age; created the world’s first wide-body in its fabled 747; ranks as America’s third biggest defense contractor behind Lockheed Martin and RTX, and has long reigned as America’s largest exporter. But Boeing is stumbling just when it should be capitalizing on the boom.

The rub is that Boeing’s quality shortcomings—and heavy dependence on a far-flung network of suppliers—are recurring and deep-seated. The problem isn’t merely that one worker on one assembly line failed to install a door screw. It was that managerial decisions, made over a period that spanned more than 20 years and four CEOs, gradually weakened a once vaunted system of quality control and troubleshooting on the factory floor, leaving gaps that have allowed sundry defects to slip through. Many weren’t related to airline safety but caused long delays; others had major and tragic consequences. “The seeds of these quality problems were planted a long time ago. These problems were hidden for years, then they exploded,” says a former top executive at a Boeing supplier.

When Boeing taxied toward “capital light” manufacturing, Wall Street got exactly what it wanted. Investors were richly rewarded; for one heady stretch in the 2010s, Boeing’s shares outperformed those of Apple, Microsoft, and Alphabet. But it would ultimately be Boeing—and its passengers—that would end up paying the price.

Boeing tries to build a 'neutral' nerve center

The structural weaknesses in Boeing’s planemaking flow can actually be quite neatly traced to strategic missteps that took root over three decades ago.

Surprisingly, the first big mistake occurred under CEO Phil Condit, an engineer steeped in the tradition of caution, safety, and excellence in design. In 2001, Condit persuaded the board to relocate Boeing’s headquarters to Chicago from Seattle, where the C-suites were a short drive to the giant plants in Renton and Everett that generated the lion’s share of revenue. The idea was to establish a “neutral” nerve center in easier traveling distance to Boeing’s other businesses, including its defense and space arm in Arlington, Va. Then in 2022, Boeing relocated again, this time to Arlington.

Shifting the top brass far from Boeing’s biggest business, and the one that’s suffered the severest problems, was a huge mistake in the opinion of several of Boeing suppliers and clients Fortune spoke to. Says a former top executive at a Boeing customer whom Fortune interviewed on background: “Why take one of the greatest manufacturing companies in the world and create a de-linkage between the leadership and the wrench-turners who make the company go?” this person asks. “That, coupled with all the outsourcing, created a kind of Frankenstein without enough command and control.”

And Boeing’s current top executives are now extremely dispersed. Though the commercial aircraft chiefs are based in Seattle, CFO Brian West and the treasurer work from suburban Connecticut, and the HR and PR heads from Orlando. It’s not clear how much time Calhoun, who served as chairman before being named CEO, spent in Renton or Everett, prior to the Portland disaster. He’s stated that Boeing’s headquarters “is wherever Brian and I happen to be.” The 66-year-old boss has two homes—one on a lake in New Hampshire, and one in a gated community in South Carolina.

A landmark shift in Boeing’s direction began when it purchased defense contractor McDonnell Douglas in mid-1997. Before the merger, the planemaker had been “an association of engineers dedicated to building great flying machines,” who put design and quality above all else, in the words of journalist Jerry Useem, who wrote a Fortune piece based on extensive interviews at Boeing in 2000, when the battle between the engineering and profit-boosting camps was storming. The prime change agent was McDonnell Douglas chief Harry Stonecipher, a 27-year GE veteran, who became Condit’s number two. Son of a Tennessee coal miner, Stonecipher expressed admiration of President Harry Truman for his decision to use nuclear weapons versus Japan. (Stonecipher famously loved delivering his variation on a quote from Truman: “I give ’em hell and tell them the truth, and they think it’s hell!”) Most of all, Stonecipher was a hawk on raising shareholder value and pushing down costs. He rallied the troops to be “less of a family and more of a team.”

Prior to the early 2000s, Boeing had built most key portions of its planes in-house, from fuselages to landing gear. As an internal debate raged over whether to embrace a new, low-cost outsourcing model, a Boeing engineer named John Hart-Smith presented a white paper arguing that the new, decentralized approach risked not providing sufficient on-site technical support and quality control of contractors. “The manufacturer is only as good as the least good of its suppliers. Costs don’t go down, because the risks are out of sight,” wrote Hart-Smith.

As president, Stonecipher—backed strongly by new director Jim McNerney, another GE alumnus—pushed for a new, “clean sheet” wide-body that Boeing could build at far lower cost than its previous version, the 777. Both Boeing and Airbus had long deployed subcontractors, though both built the major systems in-house. But for the 787, Boeing launched not just a new aircraft, but an entirely original business model. It signed “partners” who contributed billions toward the project in advance, in exchange for long-term contracts for supplying the key portions of the aircraft. Among the recruits were GE for engines, Rockwell Collins for traffic alert systems, and Spirit AeroSystems for fuselages. The new paradigm, management reckoned, would allow the planemaker to move quickly so that it wouldn’t lose orders to the forthcoming Airbus A380. By contrast, Airbus didn’t need partners for funding. It regularly secured its development backing for new models from the French and German governments.

In the 787 program, Boeing radically altered its flight plan and diverged from its chief rival by adopting a less capital-intensive model and focusing more strongly on where it could add the greatest value, in hatching the overall design and providing final assembly.

But the 787 “partnering” approach required a totally different manufacturing blueprint from Boeing’s use of subcontractors in the past. “The 787 set Boeing on its ear,” says Richard Safran, a former aerospace engineer at Northrop Grumman who’s now an analyst at Seaport Research Partners. “Boeing was saying to its suppliers, ‘You design the part or section, and tell us how you’ll build it. You need to do integration work. Now all the suppliers are mini-Boeings. They’re suddenly investing in design and engineering work, not just making the parts Boeing designed for them. It was hard for Boeing to control quality in that system, and it still is.” For Safran, Boeing never lost its talent for topflight engineering. The problem was that starting with Stonecipher, its CEOs layered on an obsession with hammering down expenses that conflicted with Boeing tradition and sowed confusion. “The cost culture was the culprit,” he says. “It started with Stonecipher, and his successors executed on it.”

Two decades of tumult

The 787 Dreamliner, and Boeing’s embrace of outsourcing, had a rocky takeoff. The plane was three years late when the airlines got their first deliveries in 2011. For several years, Boeing booked losses on each Dreamliner that rolled out from the assembly plants near Charleston, S.C., and in Everett. The extra costs ballooning from the contractors’ design miscues and production delays, along with Boeing’s errors in assembling systems made in Japan, South Korea, Italy, France, and Sweden, meant that all the outsourcing that was supposed to reap big savings backfired. In a 2011 speech, top Boeing executive Jim Albaugh stated that it never would have experienced those huge overruns if it had kept the technology closer to Boeing.

Still, the 787 proved a massive hit. “Boeing was brilliant in introducing a plane that flew direct routes and had extremely long range, while Airbus competed with the A380 that was a hub-and-spoke plane,” says Safran. “The 787 won. The airlines wanted a plane that had longer range and flew point to point.” McNerney and the new chief of the 787 program, Pat Shanahan, recently named CEO of Boeing’s troubled supplier Spirit AeroSystems, in 2008 camped out at the Everett plant and managed to get production flowing smoothly.

But for McNerney, the lingering losses the 787 generated made it essential for Boeing to escalate its war on costs. In 2011, he introduced a now-notorious initiative called “Partnering for Success” that consisted of pressuring all contractors to lower their prices, generally in the range of 10% to 15%, or even more. Those who refused often got placed on a “no-fly list” that barred them from bidding on new programs. McNerney declared that it was “out of kilter” for suppliers to reap bigger margins than Boeing. McNerney threatened to bring production of wings and other key systems in-house as a lever to garner reductions. “He kept toggling back and forth between saying suppliers are incompetent, and that we have to push out more and more business to suppliers,” says a former executive at one of Boeing’s large contractors. “Both are incorrect. You need to rely on suppliers whenever they can do things better than you can, at competitive cost.” McNerney was known both inside Boeing and by suppliers as a big picture strategist not deeply involved on the operating side. He enraged the rank and file by stating in 2014 that he wouldn't retire at 65 because "the heart will still be beating, employees will still be cowering."

In the period starting around 2011, Boeing started revving on all engines. The 787 dominated wide-body sales, and the 737 Max series, which began collecting orders in 2011 and featured the fuel-efficient GE LEAP engine, also proved a big hit, garnering huge orders from American, United, and Southwest. In 2015, Muilenburg replaced McNerney in the pilot’s seat, and continued the strong focus on lowering costs and delivering big shareholder returns. From the close of 2010 through 2018, Boeing’s financial performance was extraordinary. In that eight-year span, it multiplied its free cash flow sixfold, and its stock vaulted from $70 to $425. It posted total annual returns of 29.5%, waxing Microsoft (21.7%), Apple (19.6%), and Alphabet (18.0%). Those results demonstrate how profitable Boeing can be when not beset by quality failings.

But the eight-year run of fantastic profits was brought to a halt by the two tragic crashes in 2018 and 2019, caused by the faulty design of a new flight control software system that repeatedly pushed down the nose of the then-new 737-8 Max. Those disasters exposed the problems that had been lurking for years. And Ed Pierson witnessed firsthand the simmer building to a boil.

A whistleblower explains where Boeing went wrong

Pierson, a former Naval flight officer, worked as a senior manager on the Renton factory floor from 2015 to late 2018 during this boom period. Today, he’s executive director of the Foundation for Aviation Safety, a newly created nonprofit, and in 2019, he testified before Congress as a whistleblower, warning of potential manufacturing safety issues on the Max that he witnessed developing on the job. Those issues had everything to do with the toxic combination of a complex network of suppliers colliding with soaring demand for new planes. “The CFM LEAP-1B engines would come in late,” Pierson told Fortune. “So the planes would move down the assembly line to the next station missing engines and other parts. The workers farther back on the line had to rush down the line with their tools and interrupt the workers at the later stage to install the parts scheduled to be installed days before. That out-of-sequence work is a dangerous practice.”

He also claims that Boeing changed its inspection protocols to raise the pace. Part of the change, he says, involved laying off experienced quality control inspectors, and in lieu of the human inspections relying on a combination of “modern inspection technologies,” random statistical analysis, and more reliance on self-inspections by assembly-line workers. He notes that inspections were lowered, not eliminated. “In 2018, on weekends, we’d bring on hundreds of manufacturing employees on overtime, and we’d have less quality inspectors than we used to have, and those that remained were very overworked.”

In addition, says Pierson, Boeing did an inadequate job fixing problems identified by frontline workers. “The reality is that when workers would speak up, sometimes they weren’t listened to at all,” he observes. “Most times, they were listened to, but that didn’t solve the problem. The people they informed tried to resolve those issues, but they often didn’t get fixed, because Boeing didn’t supply the resources or capacity to do what was needed.” Concludes Pierson, “It was obviously a dangerously unstable operation. The culture on the factory floor was, ‘This is production. You need to get your job done.’”

Boeing has stated publicly that although it announced plans to lay off 900 inspectors in early 2019, it didn’t implement the plan, and has increased the number of quality inspectors 20% since 2019.

After the second crash, Muilenburg acted as if shareholders, not passengers and airlines, were his core constituency. He declared that planes’ safety systems were “designed properly” and that the pilots didn’t “completely” follow the procedures Boeing had outlined to prevent the malfunctions that cost the 346 lives. The comments didn’t sit well with the FAA. Then, in late 2019, Muilenburg publicly speculated that the FAA would return the Max to service by December of that year, further riling the agency. “I had to rein that in; I had him to my office,” Stephen Dickson, who served as FAA chief from 2019 to 2022, told Fortune. “I told Dennis, ‘This doesn’t help that you’re putting out projections on what’s an FAA decision. We’re in the driver’s seat.’ Dennis was over his skis on some significant cultural issues. They needed a change.” Eleven days later, the Boeing board fired Muilenburg.

Dickson cites that after the crashes, Boeing—in cooperation with the FAA—started implementing a new protocol called Safety Management System that encourages the line workers to report any quality issues and other safety concerns, and for Boeing to more systematically troubleshoot areas of risk around the production process. The FAA also removed Boeing’s ability to independently approve the issuance of “airworthiness certificates” that allow planes to be released for delivery, and mandated that the agency inspectors provide all sign-offs. Following the Portland incident, the FAA multiplied the number of inspectors on-site in Renton. Since the Portland blowout, Calhoun has strongly emphasized in meetings with frontline workers the importance of their speaking up on quality and safety issues.

Boeing’s shift to dependence on suppliers heightened the wave of defects that have brought so many delays, as well as steep losses, over the past half-decade. A case in point: the travails of a giant Boeing supplier, Spirit AeroSystems, manufacturer of the fuselages for both of Boeing’s bestselling series, the 737 and 787. For almost 80 years, Boeing owned the facility in Wichita where Spirit now makes those giant cigar-shaped systems. But in 2005, it sold the Wichita facility to private equity firm Onex of Canada, which took Spirit public in late 2006, and deployed acquisitions to greatly expand its suite of products and systems. “The idea was, ‘This big supplier is no longer part of Boeing, so it can also make systems for Airbus, Bombardier, and others, and hence the arrangement lowers the part of the overhead Boeing has to pay,” says Safran. “But Boeing keeps a tight relationship with a trusted contractor. It was all part and parcel of Boeing’s cost reduction initiative.”

But the grounding of the 737 Max following the fatal crashes, and a walloping from the pandemic, forced Spirit to lay off thousands of experienced production and inspection personnel. Its stock dropped almost 70% from late 2019 to the close of 2023, and it bled $1.9 billion in free cash flow. Spirit’s troubles boomeranged to plague Boeing. Starting in the fall of 2020 and into 2023, Boeing and its suppliers found quality problems, including defects in fuselages and other parts that delayed deliveries for years. Just last year, Boeing discovered mis-drilled and misaligned holes in the aft pressure bulkhead of the Max, part of the fuselages made by Spirit, that, unless corrected, could cause cracks in the bulkhead. Boeing and its suppliers corrected all problems, but the extensive rework plagued Boeing with delays and added costs.

In October, Spirit’s CEO abruptly resigned. His replacement: None other than Pat Shanahan, the 31-year Boeing veteran who’d helped rescue the 787 by swooping down on the Everett plant to smooth the production snafus. The same month, Boeing provided Spirit a sweeping financial aid package that includes an immediate cash infusion of $100 million for capital investment in tooling, and an increase in what Boeing will pay Spirit for 787 parts over the next two years of $455 million.

An anonymous whistleblower stated that during final assembly of the 737, Boeing removed the door plug to make repairs, but put it back in place without replacing any of the four bolts, so that the bolts “were not installed when Boeing delivered the plane. Our own records reflect this.” According to the whistleblower, two defect reporting systems failed, so that they never alerted Boeing quality inspectors to examine and sign off on the plug. The National Transportation Safety Board’s preliminary report, issued on Feb. 6, confirmed that Boeing workers had removed the panels’ bolts and that the bolts were missing at the time of the accident. As the whistleblower characterized it, Boeing’s production process was “a rambling, shambling disaster waiting to happen.”

Where Boeing goes from here

The outcome Boeing, its investors, and its customers fear most: a repeat of the delays that have saddled the manufacturer with giant stockpiles of planes waiting for delivery. The problem that triggered $16.7 billion in losses from 2019 to 2021 was the huge overhang of airliners Boeing was carrying in inventory. How did it accumulate that burden? Even after the first crash in 2018, Boeing kept producing planes at high speed to fulfill orders, even though the FAA’s grounding of all Max aircraft made it impossible to deliver them. It even cleared employee parking lots for storage. Then, all the quality problems, plus new FAA design requirements, and routine maintenance on aircraft stored for many months delayed delivery once the FAA approved the Max for flight at the end of 2020. Today, Boeing is still holding a gigantic 200 Max and 50 787s in inventory. The vast majority of these planes sit in what Boeing calls “shadow factories,” where they’re undergoing heavy and expensive maintenance and rework. As Calhoun put it on the Q4 earnings call, “We still have a hangover from not being able to deliver planes. In our shadow factories, we put more hours into those airplanes than we do to produce it in the first place.”

The blowout over Portland doesn’t restrict Boeing from delivering those planes, and Calhoun predicts that Boeing will send virtually all the excess aircraft to their owners by year-end. Chinese airlines have begun taking delivery on 85 Max that, caught in the trade war with the U.S., have waited parked since 2019. Even at the current low levels of production, Boeing generated a substantial $4.4 billion in free cash flow for 2023. Calhoun predicts that it can raise that number to $10 billion by 2025 or 2026, almost the average in the glory times of 2016 to 2018, and still proceed slowly and cautiously. Investors cheered Boeing’s results for Q4, 2023, lifting its share price over the following week by 5% to $211. J.P. Morgan analyst Seth Seifman doesn’t think that Boeing can rebound that fast, but still posits $8.6 billion in free cash flow in 2025.

But financial projections won’t fix the culture issues that allowed these problems to fester. Despite his disillusioning times there, Pierson is wistful about his years in Renton. “Before working in production, I worked in flight testing at Boeing Field in Seattle, with a group of exceptional professionals that benefited from solid leadership. My boss’s call sign as Navy pilot was ‘Saint,’ and rightly so, everyone loved working with the guy,” recalls Pierson. “Then, the leadership changed, and it wasn’t nearly as wonderful. People were less encouraged to speak up about problems. It’s all about leadership. Organization A has a great leader, then another leader comes in, and the organization falters.”

Pierson says that every top executive and board member at Boeing should ask themselves one crucial question to determine if they’re providing the right leadership. “The simple test is, ‘In 2023, how many times did you spend time on the factory floor and listen to the concerns of the employees who are the backbone of the company?’ If the answer is ‘no,’ you’re clearly not the right person for the job.”

But Pierson says that the culture of safety can spread through the entire company if Boeing gets the kind of leadership that once inspired the flight testing crew, leadership where the C-suite walks the factory floor, and that cherishes the expertise, and insists on getting facts and guidance from the folks who hand-make these extraordinary flying machines. In other words, Boeing can get its wings level, but only if the frontline workers have a hand on the joystick.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance