Why electric cars threaten to upend the US election

Joe Biden has called himself the “most pro-union president in American history”. He has also staked his political legacy on ushering in a clean energy revolution driven by the shift away from the internal combustion engine and towards electric cars.

Those two goals are now in stark conflict amid a historic strike at America’s biggest carmakers.

On Friday, workers at the “Big Three” auto companies, Ford, General Motors and Chrysler owner Stellantis, began an unprecedented walkout.

Some 12,700 staff at plants in the Rust Belt states of Ohio, Michigan and Missouri downed tools. The strikes, co-ordinated by the United Auto Workers union, are expected to escalate over the coming days, although plans are being kept under wraps in order to maximise disruption.

The workers have myriad grievances. They are seeking a 36pc pay rise over four years (a figure linked to what the Big Three’s chief executives are now paid), a 32-hour workweek, and more annual days off.

But looming in the background is another concern: that the generational shift to electric cars championed by Biden is a threat to their livelihoods.

The strike now threatens to become a political quandary for Biden, little more than a year before an election that will be seen as a referendum on his economic stewardship.

The Biden administration has introduced enormous subsidies both for purchases of electric vehicles and for carmakers themselves as a cornerstone of the Inflation Reduction Act, which will spend hundreds of billions of dollars on green incentives. Biden has said the programme will benefit unions, incentivising projects that have generous working standards.

But workers are not convinced. According to analysis by AlixPartners, electric vehicles require 40pc less time to assemble their drivetrains, including batteries, motors and transmission, when compared to making a combustion car with an engine.

Carmaking is also becoming more automated in general, says Peter Wells, director of the Centre for Automotive Industry Research at the University of Cardiff. Each new product line brings a more efficient process, more robots and fewer car-building jobs.

“There’s a lot of concern around what will happen with electrification – will there be enough jobs left with the workforce? Will the market be big enough? And I think, broadly speaking, the short answer is no,” Wells says.

Plenty of parts in petrol and diesel cars simply are not replicated in electric vehicles, and the jobs making these parts or fitting them to a car, will go.

“If you’re making an exhaust system, your future in new car manufacturing starts to look quite limited,” Wells adds.

New types of jobs will be created. There is likely to be a boom in software demand and other white-collar jobs. A huge potential deposit of lithium has been found in Nevada which, if proven to be accessible, could be the largest deposit in the world and enough to meet the industry’s demand for many decades.

Neither is much good to workers in Motor City, though. While Detroit and its Big Three carmakers are all unionised, plenty of other factories are not.

Newer entrants to US carmaking from Europe and Japan have tended to place their factories away from Detroit and the traditional motor making heartlands in the US, says Wells, which he adds is partly to get away from “traditional union attitudes”.

The Big Three are hardly struggling. The three companies posted combined profits of $21bn (£17bn) in the first six months of 2023, more than double the same period a year ago. It followed a run of record-breaking earnings for car companies since the crisis brought on by the pandemic.

GM chief executive Mary Barra, the highest paid of the US-based trio, now receives $29m a year, up 34pc in the last four years.

This rosier backdrop for US industry is probably what has emboldened the United Auto Workers Union to act now.

“The workforce feels both entitled to, and able to argue for, higher pay,” says Wells.

This hampers carmakers’ arguments that they have to choose between caving into unions and being left behind in the electric transition.

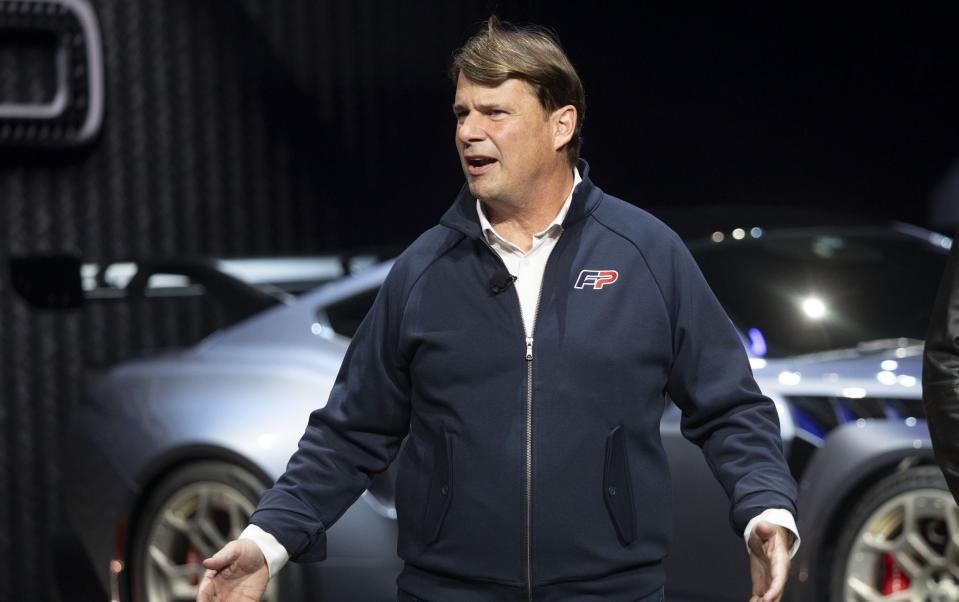

Ford chief executive Jim Farley has said that accepting workers’ demands would force it to “choose between going out of business and rewarding our workers”.

The political stakes are high for Biden. America’s carmaking industry is concentrated in a handful of states that are likely to be decisive in determining who wins next year’s election, in particular Michigan, won by Biden in 2020 and by Donald Trump in 2016. Car manufacturing is so crucial to the state that a 40-day strike in 2019 tipped the state’s economy into a quarter of negative growth.

“The Rust Belt is practically a must-win for Biden in 2024,” analysts at political consultancy Beacon Research said in a note. They wrote: “The president can’t have his cake and eat it too; his agenda comes with necessary trade-offs. Biden has to check the ambitions of his climate goals to avoid undermining political ones.”

Despite his rhetoric, Biden’s support among unions is not guaranteed. Last year the US president signed a law blocking a strike by railway workers, provoking a backlash. The UAW, which heavily backed Biden in 2020, has not yet done the same for his 2024 campaign, saying he is yet to earn the endorsement.

Trump appears determined to syphon off some of that support. The Republican frontrunner is due to give a speech to union workers next Wednesday, skipping a debate against his rivals for the nomination. The 77-year-old has said that Biden is “waging war” on carmakers with “crippling mandates” on electric cars, and has sought the union’s endorsement.

The row is a potential preview of how green issues could increasingly become a political wedge issue in the US, in the same way that policies such as London mayor Sadiq Khan’s Ulez expansion has sparked attempts to create a dividing line between Labour and the Conservatives in Britain.

Biden sees the shift to green energy as his main political accomplishment. But if voters see that push as threatening jobs – in carmaking and beyond – it will mean a political backlash that could cost him the next election.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance