One year after the Fishmongers’ Hall attack, a rethink is needed on terrorist prisoners

Up to 800 prisoners are being considered over extremism concerns at any one time

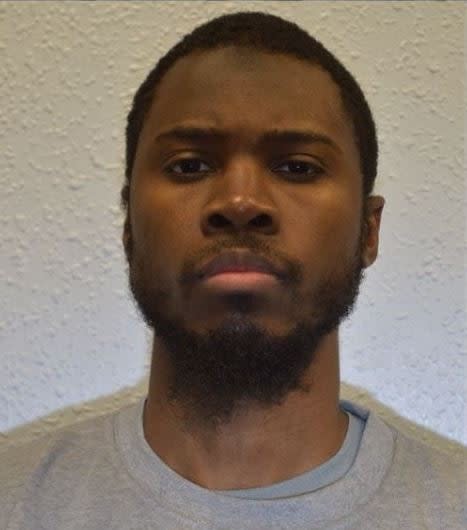

(Getty)Usman Khan appeared to be a model prisoner. After being jailed for his part in an al-Qaeda-inspired bomb plot in 2012, he had ticked all the boxes required for terror offenders.

He had been through a prison counter-extremism programme and separate scheme to reduce reoffending, and had actively asked for deradicalisation support.

In 2017, Khan went above and beyond requirements by joining Cambridge University’s Learning Together programme, going on to feature in its promotional material.

“I cannot send enough thanks to the entire Learning Together team and all those who continue to support this wonderful community,” said a thank you letter from Khan, which was published by the organisation.

But on 29 November 2019, he murdered two people who worked on the scheme at a rehabilitation event in London.

Khan arrived at Fishmongers’ Hall concealing a fake suicide vest and two kitchen knives, which he used to kill Jack Merritt, 25, and Saskia Jones, 23.

A review ahead of the inquests into their deaths heard that the agencies meant to be monitoring Khan had “no inkling” of the planned attack.

He was subject to probation management, monitoring by Prevent officers and had been “under consideration by the security services”.

Every single safeguard meant to protect the UK against terror attacks failed.

Either Khan had fooled officials by faking compliance at every step of his journey, or his reversion to violent extremism was missed.

Both possibilities should prompt a fundamental reassessment of how terror offenders are punished, managed and monitored in Britain.

Khan’s attack was the first of four by serving or released prisoners in the UK in the past year.

The second was at HMP Whitemoor, where Khan had served time, when a terror offender and radicalised inmate attempt to murder a prison guard on 9 January.

It is believed to have been the first Isis-inspired attack in a British jail, and the men’s trial revealed that they had access to terrorist propaganda inside the high-security prison.

Then on 2 February, Sudesh Amman launched a stabbing rampage on Streatham high street before being shot dead by police.

He had been released from prison days before after serving a sentence for collecting and spreading Isis propaganda.

On 20 June, Khairi Saadallah murdered three people in a Reading park in what police declared a terrorist incident.

The attack happened 16 days after he was released from prison for an offence that was not terror-related.

The attacks followed alarm over plots mounted by former terrorist prisoners and revelations that offenders have been “covering up their true beliefs” in deradicalisation meetings.

The disturbing trend is not confined to the UK. The Vienna attacker, who shot four victims dead in the Austrian capital on 2 November, had previously been jailed for trying to join Isis in Syria.

Austrian interior minister Karl Nehammer admitted that Kujtim Fejzulai “succeeded in deceiving the supervisors in the deradicalisation programme imposed on him”.

There have been no such frank admissions from the British government, which has instead been pushing to increase terror sentences and keep offenders in prison for longer.

Amid mounting concerns over terrorist networking and radicalisation inside jails, there has been no official response to calls for a public assessment of deradicalisation schemes.

An internal review of the custodial management of terrorist prisoners was launched after the HMP Whitemoor attack, but its findings will not be made public.

There are a record number of people in custody for terror-related offences in Britain, with three-quarters of the 243 inmates categorised as Islamist extremists, 19 per cent as far right and 6 per cent other.

More than 50 terrorist prisoners were freed in the year to June, and the majority of those jailed will be released in two years or less.

The most common sentence length in the latest year was under four years, accounting for 44 per cent of sentences, with 29 per cent between four and 10 years and only two people jailed for life.

The vast majority had committed “precursor offences”, such as collecting material useful to terrorists or spreading propaganda, rather than mounting plots or committing more serious crimes met with lengthy jail terms.

Whistleblowers have long warned that low-level terror offenders can become more dangerous inside prison, with one officer telling The Independent: “I don’t see any end to the attacks whatsoever, those ones that come in with an extremist view leave with a stronger one.”

The HMP Whitemoor terror attack, pictured, was carried out by a man jailed for a terror plot and an inmate who was radicalised on the inside

Metropolitan PoliceThe Parole Board sounded a warning in January 2018, during a consultation on terror sentences, saying it had “concerns that increasing the penalties for less serious offenders will result in them becoming more likely to commit terrorist acts when they are released”.

“Most of the rest of Europe is devising interventions in the community to deradicalise less serious offenders,” a document added.

“These programmes are more likely to be successful in the community than in prison, where the influence of extremist inmates is likely to be stronger.”

At the time, parliament’s Justice Committee said it had reason to believe that deradicalisation inside prisons was “absent or inadequate” and reminded the government of its obligation to consider rehabilitation as well as punishment.

“We suggest that concerns about the adequacy of deradicalisation programmes in prison may mean that the court should consider, for certain offences at the lowest level, whether it would be appropriate to impose a non-custodial sentence,” it added.

But the government has since drawn up several packages of laws adding more terror offences to the statute and increasing jail time.

Ian Acheson, a former prison governor who carried out the government’s 2016 review of Islamist extremism in jails, called them “incubators of extremism” this week.

He warned of “unimpeded proliferation of hateful ideas and images inside our most secure prisons via mobile phones and other media”.

Brusthom Ziamani, who attempted to murder a prison officer inside HMP Whitemoor, had access to Isis propaganda videos inside jail

Metropolitan PoliceSome experts believe it is time for a “fundamental rethink” of the way extremists are punished and rehabilitated, rather than continuing to push them through structures designed for ordinary crime.

Speaking at an event attended by major European politicians last week, UN counterterrorism adviser Julia Ebner suggested that security services should contact people who are being radicalised online before they commit an offence.

“It’s necessary to rethink some of these concepts and to think about other forms of intervention and deradicalisation, especially when we’re talking about online spaces,” she added. “There is a very strong need to not just focus on putting people into prison.”

The government said it had introduced the “largest overhaul of terrorist sentencing and monitoring in decades” with a package of laws currently being considered by parliament.

As well as increasing sentences, it is aiming to boost monitoring by creating a specialist division of the National Probation Service to manage terror offenders

There will also be a new Counter-Terrorism Assessment and Rehabilitation Centre for prisons, and the number of specialist psychologists and chaplains is being increased.

Separate plans for a Counter-Terrorism Operations Centre, announced in the spending review, aim to increase joint working between the security services, counterterror police and HM Prison and Probation Service.

Read More

Fishmongers’ Hall attacker visisted by police two weeks before rampage

Security review after first Isis-inspired attack in UK jail

Terrorist prisoners hit record high in UK amid radicalisation warnings

The British jail where terrorists exchange ideas and ‘jihad banter’

Terrorist prisoners free to network and radicalise inmates in UK jails

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance