How an Ex-CIA Researcher Created a Saboteur-Stopping Email Tool

"Insider threat" has become a key focus of corporate security departments. Workers who embezzle are one example of an insider threat, as are "bad-leavers"-- employees or contractors who, when they depart, steal or leak intellectual property or other confidential data, or sabotage the information technology system.

In a feature in our July issue, Fortune magazine’s Roger Parloff takes a close look at Scout, a software tool developed by cybersecurity firm Stroz Friedberg that analyzes employees' emails and, according to the firm, can spot disgruntled or unstable workers before they go rogue. Just as fascinating as the software itself are its intellectual roots--in an obscure branch of the intelligence community that specializes in analyzing the thinking of foreign leaders.

After graduating from college in 1975, Eric Shaw worked as a government contractor for the State Department and other agencies, grappling with issues related to terrorism and the problems faced by returning hostages.

Intrigued by the mental-health issues, he went back to school, earning a Ph.D. in psychology from Duke in 1984. After publishing an article on why people become terrorists, he got a call from Jerrold Post, a psychiatrist then working for the Central Intelligence Agency, where he had founded the agency's political psychology unit.

Post had pioneered an odd specialty. He and a coterie of mental health professionals around the country drew up psychological profiles of foreign leaders and terrorists to assist policy makers at the State and Defense Departments, intelligence agencies, and the White House. They tried to provide insights into the thinking of little-understood leaders like Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Saddam Hussein, or Muammar Qaddafi.

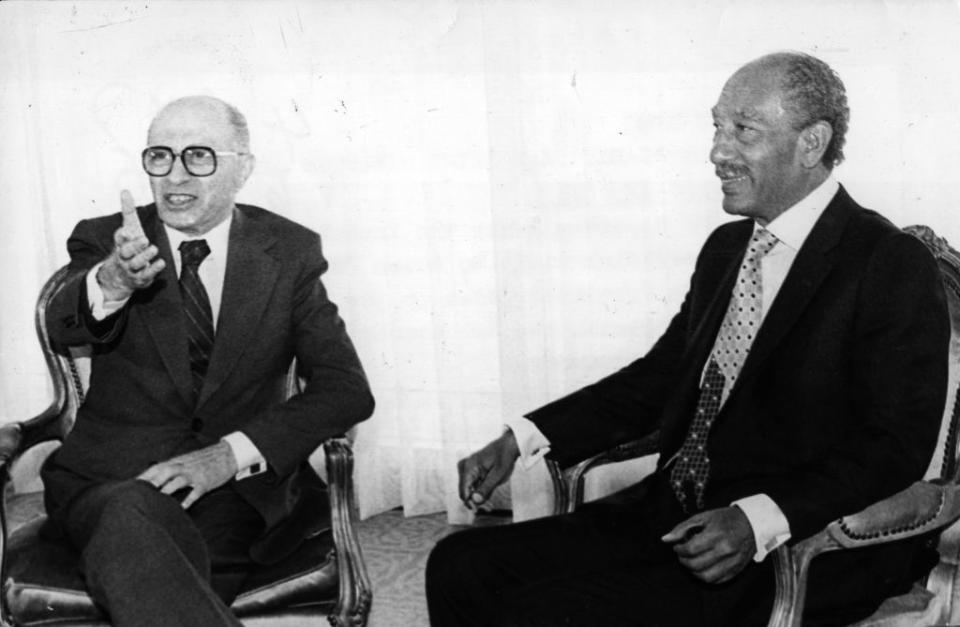

Political psychologists can’t examine their "patients" in person. One tool they use instead is language. They look for clues to a leader's personality in his unconscious speech patterns, captured at public appearances. Was he a mad man, for instance, or could he be reasoned with, and, if so, how? In 1979, Post's profiles of Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat were provided to President Jimmy Carter to help him with his negotiating strategy at Camp David.

1980: President Anwar Sadat of Egypt, right, meets Prime Minister Menachem Begin of IsraelPhotograph by Keystone--Getty Images

Post recruited Shaw to join him at the CIA in 1990. Under Post's tutelage, Shaw was exposed to forms of analysis that Shaw calls "psycholinguistics."

Clues that show anxiety

One of the academic psychiatrists who most impressed Shaw was Walter Weintraub, a professor at the University of Maryland. Among other things, Weintraub had studied the speech of hospitalized mental patients, noting distinctions between those suffering from depression, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and lack of impulse control. In his research, Weintraub found that elevated use of the word "me," for instance, was associated with passivity; was found more often in children, women, and the elderly; and could also signal feelings of victimization.

Elevated use of "qualifiers," like I think, kind of, or what you might call, was associated with indecisiveness and anxiety, Weintraub found. "Retractors," like however and nevertheless, were linked to impulsivity and "difficulty adhering to previously made decisions," Weintraub later wrote in a chapter to Post’s 2005 book, Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders. “Explainers,” like because, therefore, and since, were used heavily by didactic, apologetic, compulsive, or rationalizing speakers.

Ed StrozPhotograph by Spencer Heyfron for Fortune

After leaving the CIA in 1992, Shaw worked as a consultant to other intelligence bureaus while building a private practice and teaching at George Washington University. (Shaw says he still spends two days a week consulting for an intelligence agency which he won't identify, but which, he says, has installed his software tool Scout to monitor its own personnel’s emails.)

In the late 1990s, Shaw recounts, the Defense Department asked Shaw to study insider cyberattacks. The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s computer crime squads had the most experience with such crimes, so Shaw was put in touch with Ed Stroz, who then headed the flagship such unit in Manhattan.

Red flags for cyberattacks

The first case file Stroz showed Shaw involved a systems administrator at a bank who had butted heads with his supervisor. The supervisor eventually terminated him, prompting him to leave behind a "logic-bomb" embedded in the network, which exploded and shut down the bank's servers. Shaw examined the email traffic between the disputants prior to the termination, and then marked them up by hand to show Stroz the linguistic red flags.

"It was fascinating," recalls Stroz. At the FBI, he focused on white-collar crime, a realm in which the perpetrator's state of mind is often the only contested issue. Shaw's analysis provided entr?e into that realm. "At some point," Shaw continues, "[Stroz] is watching me code the emails and he said, 'You know, we have computers that will do this now.' That was the beginning of the idea of creating this psycholinguistic software."

Stroz left the bureau in 2000 and co-founded Stroz Friedberg, which today has more than 500 employees in 14 offices–and which eventually partnered with Shaw to create Scout, a psycholinguistically oriented email scanning tool. Read Fortune's feature, "Spy Tech That Reads Your Mind," to learn more about Scout's potential and its pitfalls.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance