Gamification is a Dirty Word

Nils Pihl founded Mention LLC, a Beijing-based international consulting agency specializing in engagement design and behavioral engineering.

Every now and then a word comes along that captures the imagination of everyone it touches. Almost overnight these words spread across our collective consciousness and alter the tone and content of our conversations. Gamification is one of those words, and it has completely hijacked and derailed many meaningful discussions.

The proponents of gamification rightly point out that there are opportunities to learn from games, ways that we can make our products more engaging, and that an increased awareness of what makes games so engaging could help us solve a lot motivational problems that we are struggling with. By unraveling the substance of games we can use these building blocks, popularly called game mechanics, to build a new generation of products.

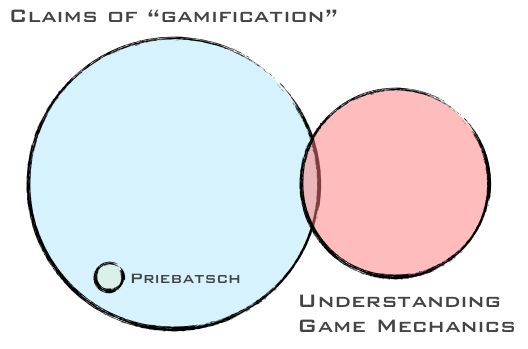

The problem is that the proponents of gamification don’t actually understand the substance of games. In their enthusiastic fervor they have mistaken some of the least important parts of games - things like leaderboards, points, and badges - as the essence of games. Margaret Robertson rightly called the movement out in her entertaining piece on why it should be called “pointsification” instead. Others, like Ian Bogost, have said that even that would be too kind, arguing that “exploitationware” would be more descriptive. There is a huge discrepancy between the people who understand, master, and use game mechanics, and those who claim to be able to gamify your product.

The entire edifice of gamification is built on investor hype, anecdotal evidence, and the opportunistic exploitation of a powerful new word without a clear meaning. Millions of dollars have been poured into companies with cheap first-to-market technologies, regardless of how shallow and superficial their understanding of the problem at hand is. Badgeville, a company whose name itself is an affront to people who make a living making engaging experiences, raised 15 million dollars in venture in their first year of operation. The leaders of the movement, people like Gabe Zichermann, are happy to toot their own horn and describe a future economy where gamification will one of the most valuable skills on the market. Bullish analysts caught up in the craze are fast to follow and give astronomical market caps for an industry that no one has really bothered defining. At no point during all of this do the enthusiasts stop to look at how vacuous Zichermann is.

The presence of key game mechanics, such as points, badges, levels, challenges, leaderboards, rewards, and onboarding, are signals that a game is taking place.

Say it often enough and it will be indistinguishable from the truth. Zichermann wants us all to believe that the things that are the cheapest to program and implement just so happens to be “key game mechanics.” Make no mistake about it, the reason these things are touted as important is not because of their proven effectiveness, but rather because of how cheap, scalable, and attainable the technology is. Zichermann goes on to argue that gamification has “Armed [marketers] with a new understanding of what people tick, and how to wind them up,” and they can now build experiences that are both enduring and engaging. But where is implied understanding? What deep insight of human psychology can you really glean from the anecdotal evidence you are marshaling?

The sad truth is that there are no one-size-fits-all solutions, and the art of making engaging products and games remains well outside the abilities of the hundreds of opportunistic bandwagon passengers that try so hard to dominate the discussion.

Other enthusiasts, like Seth Priebatsch and Jane McGonigal, step up on the popular stages like TED and spread the word. The problem is, for all the enthusiasm that they bring to the topic, that they do the topic a disservice by oversimplifying or being straight out wrong.

I can attest to the fact that it is possible to make a living helping companies make more engaging products, and learning from games is a great way of getting there. There truly are some deep, intractable truths at the core of game design that can be applied to a variety of other designs - but “gamification” is a word that has derailed the conversation, polarized the community, and created unhealthy expectations in both designers and customers.

Quite frankly, I am tired of cleaning up the mess that people like Priebatsch have created.

The metric for measuring your progress in a game is not what makes the game. Implementing a leaderboard on your website will probably not make people buy your product. A badge is no substitute for quality and substance.

What we can learn from games lies at the very core of what a “game” is:

When all the fluff and marketing hype is peeled away, a game is a system where we voluntarily engage in something to receive a perceived reward. We can learn meaningful design lessons by understanding the difference between work and play, and by realized that the reward is always a subjective thing brought to the table by the player.

What we can learn is that making a product engaging means understanding what brought our users there in the first place, and enforcing those structures by clearly communicating how they can get what they came for.

Ask yourself: Did your users come to “earn points”?

I must admit at this point that I was once very excited to see how the word gamification gained popular acceptance. I thought, for a while, that this new vocabulary addition would make it easier for me to explain some of the more arcane and mystical aspects of product design - The opposite has happened: I spend more and more time having to deconstruct the many mistakes that seem to accompany familiarity with gamification.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance