This is why we need better on-screen dads

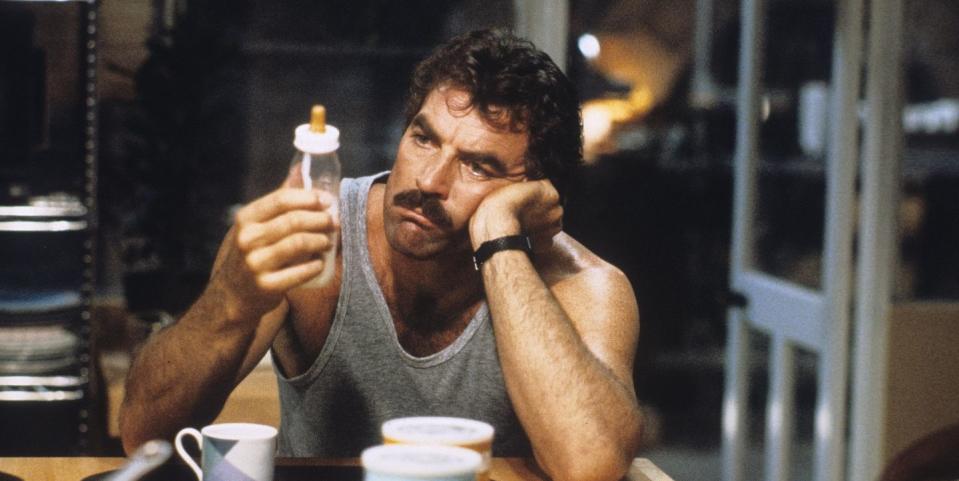

I used to watch Three Men and a Baby on repeat when I was a child. I loved it. Sure, it’s a certified eighties classic. Sure, Ted Danson looks cute as hell, so does Tom Selleck, and sure, we all forget the name of the other one, but for me, the appeal lay in the fact it was the only time I saw a man caring for a baby on screen. This was important for me. Because in life, the only other man I saw caring for a baby was my father, a stay-at-home dad.

We know too well that representation matters. Yet the representation too rarely discussed is that of on-screen fathers. This was problematic to me from a very early age. Even the first half of my beloved Three Men and a Baby rankles, as the comedy is mined from – and indeed the entire plot is predicated upon – the assumption that men are terrible with children. Even as a five-year-old I knew this was ridiculous. Yet this ingrained societal misconception has become the scaffolding for generations of unequal parenting.

Dads on screen tend to be inept. They get nappies stuck to their heads, they flood bathrooms, burn food, loose kids, blow up or shrink the kids if you happen to be Rick Moranis (yes, I watch a lot of eighties movies). This comedic trope becomes a dangerous ideation as it informs our view of men as parents. All this repeated imagery of feckless men contributes to the idea that women are natural born caregivers and men are simply affable extras who will occasionally sub in and cause mayhem and mischief. Even Moranis has to say ‘honey, I shrunk the kids’ as though apologising for damaging his wife’s property. Other than that, fathers then don't seem to factor in a child's life on screen until they are themselves adults; like Father of the Bride.

I saw this stereotype time and time again and was then confronted with the opposite truism everyday – my father. My dad gave up work for the first five years of my life in order to be a full-time parent. He was, and still is, a fantastic dad. He changed nappies, did bottle feeds, did nursery drop off and pick up, playground visits, play dates, the lot. Yet he was the only father at the school gates and was treated as a novelty. He was my in-case-of-emergency contact, and the school still called my mum, as though my father was a paltry substitute for a mother. At every opportunity, I was confronted with a societal bafflement regarding my dad, as though he was an aberration. I was repeatedly asked, by students, teachers, fellow parents, if my mother was dead, if my parents were acrimoniously divorced. They simply couldn’t fathom that a man could be happily married and take on the primary caretaker role. After all, why wasn’t he running around the supermarket like a bemused Tom Selleck, desperately asking women for help with nappies? How was this man being a capable father?

Even stay-at-home dads get a bad rep on screen. My favourite TV show of recent years is Motherland and – while I adore it – the character of Kevin makes me squirm. The only full-time father, he is portrayed as weak, silly, neurotic. He is almost, dare I say it, a bad stereotype of a woman – an overly emotional wreck. What we draw from this is that any man willing to care for a child full-time must somehow become a crudely drawn clichéd female to do so. Once more, caring is illogically still gendered. At a time where we are desperately trying to move the needle forward on equitable parenting, these consistent depictions of feckless or weak full-time dads is regressive and detrimental.

This week, to coincide with Father’s Day, a new film, Fatherhood, based on a true story, is released on Netflix. Kevin Hart plays a widowed dad, whose wife dies giving birth to their daughter. His is an at-times clichéd take on struggling to adapt to fatherhood but the film largely depicts the power men have within them – much like women – to be excellent parents. It is a heart-warming tale, and a worthy addition to the canon of good on-screen dads. Yet it still bothers me that the idea of a man taking on the care of his daughter is still novel enough to be the entire plot line of a film. Films like this, characters like Kevin, show that men being fathers is still far from being normalised.

This Father’s Day, I will be thanking my dad for being a dad, not an occasional substitute parent. He deserves as much praise and delight as any woman on Mother’s Day and I hope that someday soon this is a reality for more and more families. Because this is bigger than just looking for change in paternity leave; this is a need for a huge societal rethink in how we approach parenting. We can only treat men as parents when we start really thinking of them as parents in the same way we do women. And we can only get there by seeing more men as capable dads – on screen and off.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance