Are we underestimating the impact of climate change? Schroders thinks so

A number of cold countries — which coincidentally happen to be most of the developed economies — face more severe economic damages

Concerns around the growing impact of physical risks associated with global warming call for a more in-depth analysis of their potential economic consequences, writes Irene Lauro, environmental economist at Schroders.

Global average surface temperature rose by 1.45°C above pre-industrial levels in 2023, making the year the warmest on record. As global warming intensifies, extreme weather events have become more frequent and their economic damage more significant, says Lauro in a note released June 20. “With climate change becoming a more pressing issue, it is extremely important for investors to understand its impacts on the economy when making asset allocation decisions.”

This is not new. But climate scientists are forecasting things will get a lot worse a lot sooner than many mainstream economic models predict, according to Lauro.

Economies and financial markets face greater downside risks, says Lauro. “There is uncertainty in all of these projections, and this is only one possible scenario. But investors should understand how their portfolios could fare if the forecasts of climate scientists materialise, and what steps they can take today to mitigate against the risks.”

What do popular economic models predict?

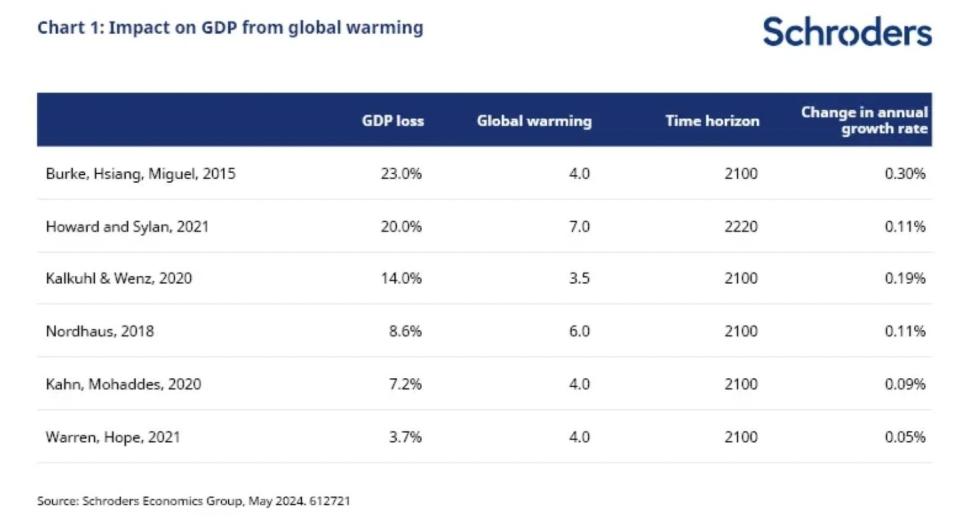

While there is a strong consensus that a warmer world means a poorer global economy, economic estimates tend to lie in a very broad range, says Lauro. “This is unsurprising given the high degree of uncertainty surrounding future climate scenarios and the deep link between various sectors and ecosystems.”

For example, the total loss in global GDP by 2100 with a 4°C warming is estimated to be between 4% and 23%. While a 23% drop in GDP might seem a big hit to the economy, when looking at the annual damage, the economic cost is estimated to be less than 0.4% per year, even in the most severe case estimated by economists, says Lauro.

This is in contrast with the expectations of climate scientists, who are forecasting mass extinction if temperatures rise more than 5°C from pre-industrial levels. While 5°C would be towards the upper end of the figures in the table above, the impact on GDP would obviously be far greater than any of these figures suggest, Lauro adds.

Lauro cites a group of international scientists from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and the Stockholm Resilience Centre, who have predicted that even at 1.5°C, economic models are overlooking the “true degree of risk”.

When large parts of the climate system cross a warming threshold and start to change by themselves, this is called a tipping point. There is a significant likelihood at these temperatures of passing multiple climate tipping points, particularly around major ice sheets, says Lauro.

Another international team of scientists predicts that even if the carbon emission reductions called for in the Paris Agreement are met, there could be a severe climate impact. For instance, within the Paris scenario, there is a risk of Earth entering what they call “Hothouse Earth” conditions, where sea levels would increase by 10 to 60 metres.

Revising the damage from climate change

Lauro says there are growing arguments from climate scientists that the physical risks of climate change could be much higher and be distributed differently around the planet.

Firstly, confidence is increasing among climate scientists that, as temperatures rise more than 2°C above the pre-industrial level, the global economy is likely to be negatively impacted by changes in the physical environment.

Lauro says scientists are now more confident that rising temperatures will result in stronger tropical cyclones, extreme heat impacts and more frequent and intense floods and droughts. In addition, they increasingly believe global warming will result in the destabilisation of ice sheets and glaciers and consequent sea level rises.

Secondly, most of the damage functions used by policymakers to quantify the risk the economy faces as a result of climate change only look at global average surface temperatures, says Lauro. They exclude other important measures, such as temperature volatility.

This matters as temperature volatility directly impacts the frequency and severity of extreme weather events. This second factor could have a profound and negative impact on the outlook for colder countries in particular, and developed markets would be the most affected.

Impact on GDP

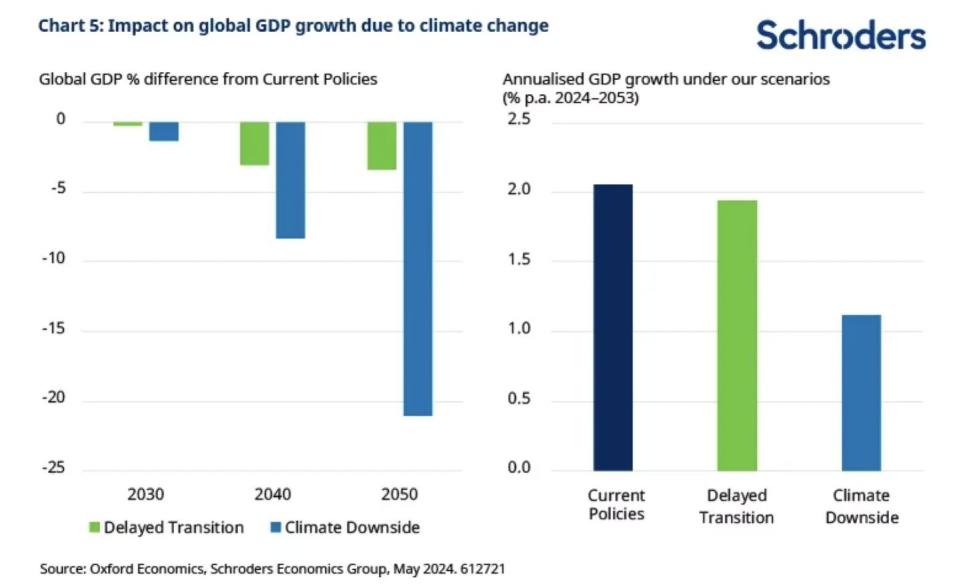

The higher level of warming and the adoption of a damage function with temperature anomalies lead to a more significant impact on global GDP, says Lauro.

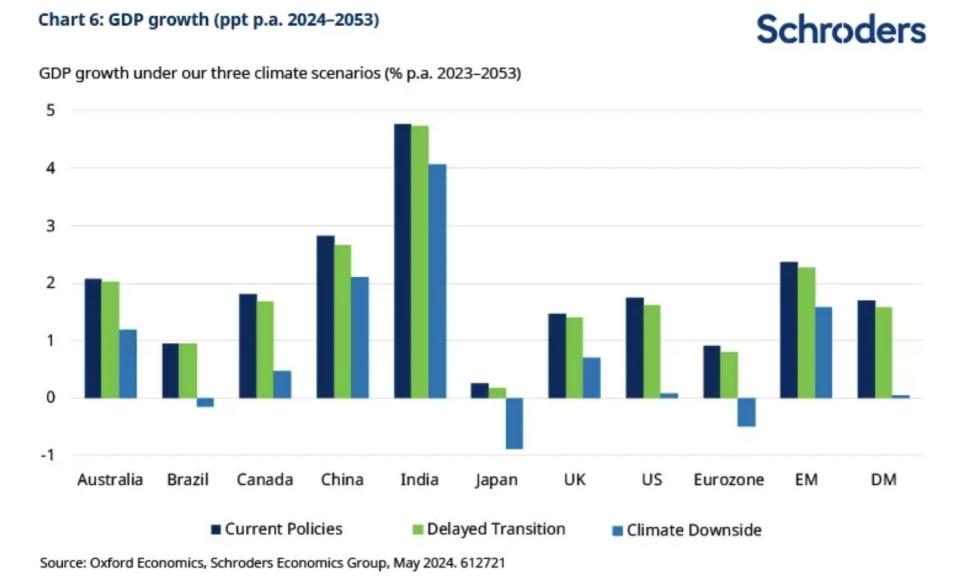

With the application of the revised damage function, a number of cold countries — which coincidentally happen to be most of the developed economies — face more severe economic damages.

Canada, the US and the Eurozone are forecast to see the largest hit to GDP in one of Schroders’ scenarios. This is due to the fact that they are likely to warm up faster than others, being closer to the Arctic, the fastest-warming region of the planet, says Lauro. “A quicker rise in temperature for regions in the northern hemisphere means higher temperature anomalies and volatility and therefore more severe extreme weather events hitting these economies.”

What does it mean for inflation?

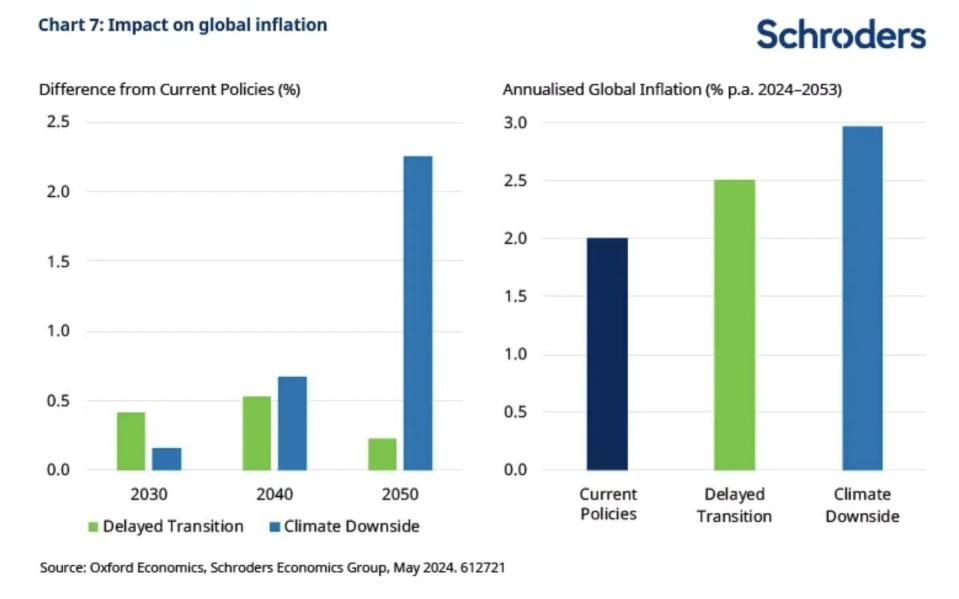

Transition and physical risks have a significant effect on economic output, and they will also influence inflation. The impact on inflation is initially much higher in Delayed Transition than in Climate Downside. This is because, in the transition scenario, we see a sharp rise in carbon prices starting from 2030, which leads to escalating energy prices. As economies tend to move away from fossil fuels and start to rely more on cleaner energy sources, the impact on inflation declines in the transition scenario.

In comparison, inflation tends to increase in Schroders’ scenario over the next decades due to the escalation of temperature rises and the greater volatility in temperature changes.

“More frequent extreme events lead to resource scarcity, notably around the availability of water, arable land and certain commodities, which results in cost-push inflation,” says Lauro. “As temperatures rise, input prices follow suit, leading to supply-side shocks that intensify over our forecast horizon.”

The Eurozone, Japan and Brazil are forecast to have outright negative growth over the next 30 years in this scenario. The US is barely positive. The downside risks should not be underestimated, says Lauro.

What does it mean for investors?

Schroders’ analysis suggests investors will find it increasingly challenging to generate returns in excess of inflation at the levels they may be hoping for. This highlights the importance of incorporating physical risks in strategic asset allocation decisions, says Lauro.

From an asset allocation perspective, the balance shifts in favour of emerging market equities over developed markets in this scenario, she adds. “A stagflationary environment is also likely to make bonds a less reliable diversifier of equity risk.”

Lauro hopes this analysis serves as a “wake-up call”. “Rather than the relative lack of response from policymakers, which is assumed in this scenario, one would hope that physical consequences on such a scale would spur a reaction, albeit things may need to get worse to force this response.”

Charts: Schroders

See Also:

Click here to stay updated with the Latest Business & Investment News in Singapore

Schroders bags four awards, unfazed by high interest rate environment

Companies committed to engagement set climate targets faster, post better returns: Schroders

Get in-depth insights from our expert contributors, and dive into financial and economic trends