Shuggie Bain’s tale tells us that the Booker prize has matured

Representation in fiction: why does it matter? The reasons are legion, and obvious. If, for example, you grow up reading books in which you see nobody who looks – either literally or figuratively – like you, then there are consequences. It shapes your idea of a default citizen, of the value of who and what is written about, and of the hierarchy of imaginative possibility. And if – as artists and those who follow them largely believe – the imagination should be a place of liberation and equality, in which language and ideas are the only currencies worth anything, that is a problem.

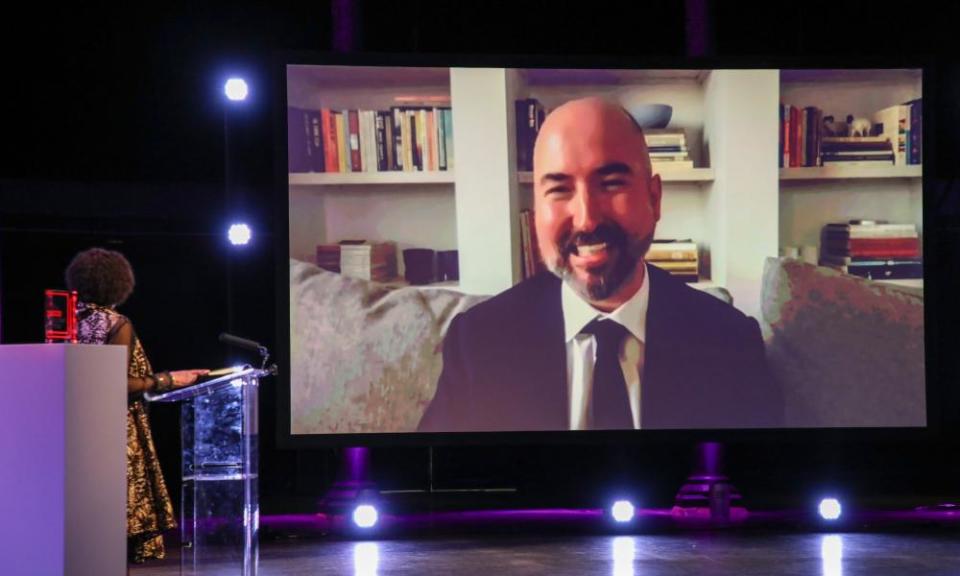

It was for Douglas Stuart, whose debut novel Shuggie Bain won the Booker prize last week. Stuart has followed the classic trajectory of the overnight success: now 44, he wrote his book only after overcoming his internal feelings of illegitimacy – the common anxiety that amounts to an anti-entitlement, a belief that writing novels is for other people – and then saw it rejected by numerous publishers. His life was hardly a bust – he had left his native Glasgow for New York and became an accomplished fashion designer – and yet, he wasn’t a novelist.

But creativity doesn’t always operate to a speedy timetable. Shuggie Bain draws heavily on Stuart’s childhood and the struggles of his mother, who died when he was a teenager after suffering from alcoholism for many years; it has been widely described as a love story, a tribute to a life whose difficulty did not diminish its value nor its deep attachments. To paint a broad brushstroke, material as intense and complicated as this seems to translate into fiction either in a sudden flood or over a long-drawn-out period.

There is a recalibration of the idea of big names duking it out, talent slighted or celebrated, scores settled

All writers must find their own course. But it’s harder without a guide. For Stuart, that was the novelist James Kelman, until Thursday the only Scottish writer to have won the Booker prize, for How Late It Was, How Late, a quarter of a century ago. Stuart, whose fictional landscape is working-class Glasgow in the 1980s and 90s, has said that the novel changed his life; and the experience of seeing “my people, my dialect, on the page” clearly lodged in his brain.

It’s easy to think the Scots were always there or thereabouts in the game of literary reputation; voices as diverse as Irvine Welsh, Ali Smith, Val McDermid, AL Kennedy and Ian Rankin make one think of long careers, excellent reviews and vast readerships. But when How Late It Was, How Late won the Booker in 1994, it was a shock, and not only when it was announced; during the judging process, Rabbi Julia Neuberger walked out, subsequently dissociated herself from the winner and branded the book “crap”. Writing a few years ago, another judge, the critic James Wood, remembered Kelman turning up to the black-tie ceremony in an open-necked shirt and using his speech to lambast the establishment: “My culture and my language have the right to exist, and no one has the authority to dismiss that … A fine line can exist between elitism and racism. On matters concerning language and culture, the distance can sometimes cease to exist altogether.”

There were, apparently, no such schisms in the awarding of the prize this year – luckily for the Booker, which has only just got over the brouhaha of last year’s split decision, which saw the award go to both Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo after the panel’s mutiny against the rules.

Related: Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart review – lithe, revelatory debut

But perhaps that’s also because of the subtle, glacially slow collapse of the winner-takes-all mentality of high-profile prizes. This year’s Booker shortlist was heavy on debut writing, on women, and on writers of colour. One of the unexpected results of this gradual, overdue widening of the publishing world is that the sense of a joust loses its power; there is a recalibration of the idea of big names duking it out, talent slighted or celebrated, scores settled. Once, the gossip around the Booker prize tended to centre on who cut whom dead at the afterparty, and which agent shouldn’t sit next to which editor next year; maybe now the invitation list is bigger and the guests, so to speak, can wear what they like, we’ll all have a better time.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance