Retire today and you're 46pc worse off than 10 years ago

Ten years on from the collapse of Northern Rock, the devastating impact of the financial crisis on the pensions of savers approaching retirement is only now becoming clear.

A potent mix of record-low interest rates, stagnant wages and rising inflation has left pension investors a staggering 46pc worse off than those who retired before the crisis, analysis compiled exclusively for Telegraph Money reveals.

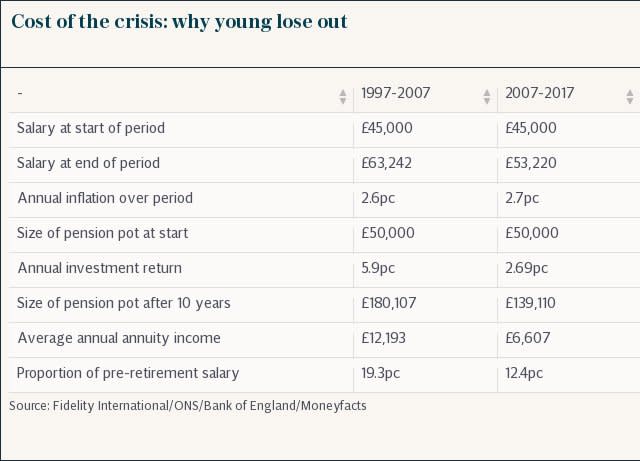

The research, conducted by Fidelity, the fund manager, shows that a typical pension pot in 2017 would be able to produce an annual income of only £6,607, only just over half the £12,193 retirees in 2007 enjoyed. The analysis compares the 10 years before 2007 – the year when Northern Rock imploded and the US investment bank Bear Stearns realised it was in trouble – with the past decade.

It assumes that someone with an existing £50,000 pension pot and a salary of £45,000 is saving 12pc of their wage into a pension. Average earnings rose by 3.5pc a year between 1997 and 2007, according to the Office for National Statistics, more than keeping pace with inflation, which averaged 2.6pc over the same period.

But while salaries grew by 1.7pc between 2007 and 2017, the cost of living rose by 2.7pc annually, meaning that workers suffered a pay cut. Falling real wages were exacerbated by lower investment returns. A typical pension portfolio comprising 60pc global stocks and 40pc global bonds returned 5.9pc a year in the decade to 2007.

However, returns on the same portfolio nearly halved (with returns of 2.7pc) the following decade. Lower wages, and in turn lower levels of pension savings, combined with weaker investment returns, mean the younger saver ends up with £40,997 less than their older counterpart, with a final pot worth £139,110 against £180,107.

Using historic market rates for annuities – insurance contracts that pay a guaranteed income for life – the research shows how much the savers would have to live on in retirement.

In 2007 the average non-inflation-linked annuity rate for a single person was 6.8pc, according to Moneyfacts, the data firm. At those rates your pot could buy an annuity that paid £12,193 a year.

While rates have increased this year, they are still far below pre-crisis levels at 4.75pc. The smaller pot saved by 2017 would produce an income of only £6,607 a year in today’s market.

“Sometimes it’s better to be lucky than good, and those who retired before the financial crisis have certainly been luckier than those who followed them,” said Fidelity’s Ed Monk.

“We already knew that those safely retired by 2007 were more likely to have gained from generous ‘final salary’ pension schemes. This work shows that even on a level playing field where a pension pot is invested, poor wage growth and lacklustre markets have conspired once again against younger savers.”

Why are annuity rates so low?

Insurers peg annuity rates to the yield on long-term UK government bonds, known as gilts. The firms have to hold these bonds against their annuity promises so if gilt yields fall, as they have fairly steadily since 2007, they have less to pass on to customers.

There are several reasons gilt yields have fallen over the past decade but the most significant is the action of the Bank of England in the wake of the crisis. It cut interest rates and bought billions of pounds worth of gilts as part of a “quantitative easing” policy designed to prop up the ailing economy.

While mortgage borrowers have largely benefited from suppressed rates, savers, bondholders and pensioners have borne the brunt of the Bank’s actions.

Better rates are available to those who qualify for enhanced or “impaired life” annuities, which offer higher rates on the basis that they won’t have to pay out for so long.

Why the pension freedoms ease the problem

It was this perverse situation, repeatedly highlighted by this newspaper, that appeared to nudge George Osborne, the former chancellor, into announcing the “pension freedoms”.

This sweeping set of reforms, in force since 2015, ended the effective compulsion to buy an annuity. The freedoms ease the pressure on the younger age group, who can instead leave their money invested into retirement.

Mr Monk said: “With ‘drawdown’ you have the option to take a regular income from your pension while keeping the rest invested. Money you leave inside your pension could then continue to grow. This comes with greater risk, but at least provides an alternative.”

Since 2015 most people have chosen to go into drawdown rather than buy an annuity. Yet the City watchdog has expressed concerns over investors doing so without the help of financial advisers.

The fear is that “DIY” investors have constructed vulnerable portfolios that will suffer big losses if there is a sudden market correction.

Fund shops, including Hargreaves Lansdown, Britain’s largest, have also warned of strict rules that can prevent them from intervening when elderly or vulnerable customers withdraw too much cash or take risky decisions.

sam.brodbeck@telegraph.co.uk

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance