How Not to Be Anthony Bourdain

Do you want to know the real Anthony Bourdain? Think before you answer. You and I and millions of others thought that when Anthony Bourdain lived, we knew how. We saw him living his life louder, bigger, more than we did, on his shows and speaking tours, read it in his books, absorbed it from his go-forth-and-fucking-do spirit. Then he died by suicide in 2018, and a hairline fracture formed between our Bourdain and this other, apparently life-disdaining Bourdain. Three years later, the documentary Roadrunner came out and revealed the ugly but very real end of Bourdain’s life, and it jammed an icepick deep into that fissure. The man seemed to have day-dreamed about death as much as he’d lived his life. Now different books from two different people, both with the authority to discuss Bourdain’s life, join Roadrunner in reconsidering the man by first tearing him down, then rebuilding him as a god. Like all mythology, they thump with the queasy, the uneasy, and an undercurrent of reality.

So, Bourdain fan, do you want to know more?

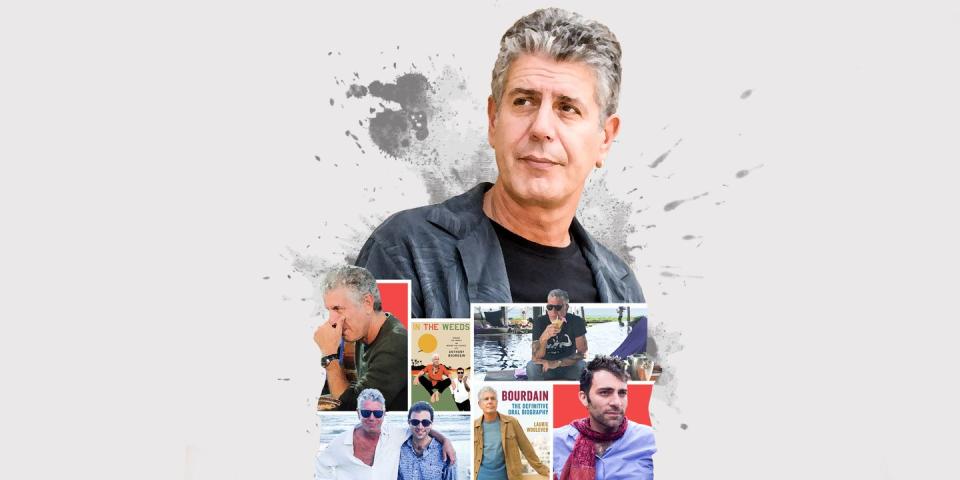

The first account comes to us in Bourdain: The Definitive Oral Biography, put together by his former assistant Laurie Woolever, and featuring the testimonies of 91 comrades, colleagues, ex-wives, and friends. The book strains to be frank about the fact that Bourdain was rarely easy on those around him, but it also gives plentiful space to its cast of characters to build up the god among men mythos as well. In a representative account, Tom Vitale, longtime director of Bourdain’s various television shows, says halfway through the book, “There was a sort of a sadistic element to the job and the relationship.” Sort of. That’s a hedge. The quote continues, “But the way I look at it, it relieved pressure from him, that someone else was suffering a bit, too, because it was a tough job for him.” A bit. This is putting it mildly.

The second addition to the Bourdain-osphere is Vitale’s own book In the Weeds, a tale of Vitale’s 15-plus years working with Bourdain and then teetering dangerously on the verge of emotional collapse in the aftermath of Bourdain’s suicide. In the reading, it becomes clear that Bourdain put him and the rest of the crew through psychological—and at times, bodily—warfare.

The stories Vitale has to tell are incredible. Vitale trapped in Transylvanian torture stocks, Bourdain whacking him with a pitchfork. Bourdain commanding Vitale to “Do it faster!”—”it” being saw off a live chicken’s head with a egregiously dull knife blade through panicked tears on a riverboat in the Congo. Bourdain full-body tackling Vitale at a village festival in Borneo, strangling him until other crew members pulled him off, livid that Vitale had lost his cool about getting an earlier shot. The Bourdain that emerges in In the Weeds is a bully. That, or a sadist. “Is there such a thing as vacation-of-a-lifetime PTSD,” Vitale wonders about his job in a chapter that’s titled Signs You’re in a Cult, “where your main tormentor is also your hero, mentor, and boss?” That’s the real revelation; Vitale gave Bourdain an out for his behaviour each time. He seems to know he’s doing so, but can’t seem not give him that out. “Tony’s leadership techniques were CIA caliber: duplicitous, unforgivable, possibly criminal, and usually extremely effective,” Vitale writes.

As Bourdain demanded his viewers not be queasy about whichever corners of otherness around the world he was featuring on his show that week, he demanded his crew perform stomach-turning feats, like hanging out of airplanes and off car roofs to get a shot, or endangering local guides for access, or cutting off the head of a chicken while blood spurts and its still-alive eyes bore into yours, wondering what it’d done to deserve such a gratuitous slaughter. It is engrossing reading material, until you remember we’re talking about actual people who created television for our viewing pleasure. But that is the trouble that becomes inescapable amongst all this posthumous Bourdain content; he was real and the people around him were too.

Woolever’s Bourdain is rife with these types of stories too, though they tend to gloss over the details of an encounter for the sake of furthering the anecdote along. After all, this oral biography has a lot of ground to cover: It starts at his parents’ marriage and ends with Bourdain’s daughter, Ariane Busia-Bourdain, reflecting on her now-deceased father’s legacy. Woolever herself stays at arms length, to powerful effect, giving her cast of characters room to air their Bourdain grievances, both petty and life-altering, and unroots some rather profound conclusions—almost Parts-Unknown-narration-level profound—about the man.

“Just as comedy often comes from a dark place, if you are entirely content, you don’t spend two hundred days a year traveling the world,” CNN’s Anderson Cooper theorises in Bourdain: The Definitive Oral Biography about Bourdain’s relentless pursuit of experience.

“He banded [all] these people, without banding them together. Maybe that’s the problem… No one was sharing info about him. And so, he had access to us all, we had access to him, but not each other. And so, there was no life raft. He was on a rowboat alone. And I fucking hate that. Because he wasn’t alone. He just felt he was alone,” musician Josh Homme says in the same book of Bourdain’s self-banishment in a sea of people who cared about him. “He could have weathered that storm if he was on the life raft that he actually built.”

There’s a paradoxical pain built into reading a biography of someone we thought we knew well: In getting to know him better, he somehow morphs into a stranger. The strangeness here, though, doesn’t quite come from the fact that Bourdain treated those he loved recklessly. Or that the man who charmed us in his 1999 description of why never to eat mussels on Mondays was clearly stuck so deep within his own celebrity he couldn’t see how that celebrity affected the way he treated others. The most difficult part to process for Bourdain fans isn’t even the pains his tormentees take to explain away his shortcomings. The greatest strangeness here is that the most steadfast fans of all might be compelled to rethink their admiration, which three years ago was unthinkable. The line of what one fan can tolerate might have been crossed, just as Bourdain’s comrades flirted with that line time and time again.

Besides a comprehensive biography—of the heroin years, the fame monster years, the family man years, the Asia Argento years—Bourdain offers the explanation that these people had learned so much from Bourdain, but he never seemed to learn the most important lessons from them—that they’d follow him anywhere, that they’d transformed their lives for him, that they loved him despite all the fuckery. Vitale certainly did.

Despite the seemingly unforgivable extremes, Vitale had seen Bourdain as a role model for his entire adult life. “I had looked at Tony, his triumphs, and my place in his band of misfits as proof I was on the right track,” he writes in In the Weeds. “Knowing now where Tony’s path had ultimately led, I was left to question the wisdom of my own choices.”

So here we all are, questioning the mythology of a man whose lifestyle we collectively admired, but who seemed to treat the people who cared about him recklessly. There’s a lot of anger there. There’s a lot of self-examination to go around. There’s a lot of what feels like people tripping over themselves to explain away his volatility (particularly amongst his vast behind-the-scene crew), or else unwittingly admitting to saintlike visions of him (more prevalent amongst his celebrity friends).

Bourdain forfeited control over his own mythology when he died. And within these personal reckonings there are some intimate moments that he might’ve not wanted on the record. The grease spot his hair gel left on the window of the van the crew drove around various countries, revealed in Woolever’s oral biography springs to mind; along with his fanboying about speeding through New York City with Bill Murray behind the wheel; and his nerves before the iconic Vietnamese dinner with President Obama, detailed by Vitale. The way he pushed people away before the end, and how now, Bourdain the man as an idea is in the hands of their memories.

Many of us wanted to be like Bourdain. These books, taken together, also warn us to steer well clear of the bad.

If you or someone you know is struggling or just needs to talk, please call the Samaritans at

116 123.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance