Jehan Sadat obituary

Jehan Sadat, who has died aged 88 of cancer, spent most of her life promoting social justice and women’s rights in Egypt. She continued to campaign decades after her husband, President Anwar Sadat, was assassinated, on 6 October 1981, by militants in the army avenging the imprisonment of fellow Islamists and condemning the 1978 Camp David accords that he had signed with Israel.

As a girl in Cairo, Jehan had explored the streets of her neighbourhood of Al-Manial, attributing her self-confidence to her supportive parents. She said that her fight against gender inequality started during her schooldays, when she was encouraged to focus on subjects such as sewing and cooking in preparation for marriage rather than the sciences that would lead to a university career. “I have always regretted that decision. I would never allow my daughters to close off their futures that way,” she wrote in her autobiography, A Woman of Egypt (1987).

Jehan had married Sadat in 1949 at the age of 15; a former army officer, he was twice her age and active in the fight against British control in Egypt. Three years later, he was a key player in the military coup that toppled King Farouk and later brought Gamal Abdel Nasser to the presidency. Sadat took a series of senior positions in the government and after Nasser’s death in 1970 was elected president.

Jehan had begun her work for women’s rights in the years before she became first lady. She was vocal in condemning female genital mutilation and played a crucial role in the 1960s in the formation of a co-operative in the village of Talla in the Nile Delta that helped local women become skilled in sewing and therefore economically independent of their husbands.

She also headed SOS Children’s Villages, an organisation that provides homes for orphans in a family environment. In 1975 she led the Egyptian delegation to the UN international conference on women in Mexico City and to the 1980 conference in Copenhagen.

Most crucially, she was involved in a campaign to reform Egypt’s status law that would grant women new rights to divorce their husbands and retain custody of their children. The 1975 film Oridu Hallan (I Want a Solution), starring Faten Hamama, illustrated the struggles of Egyptian women under a conservative legal system that suppressed their rights.

Egypt will not be a democracy until women are as free as men

“Over half our population are women, Anwar,” she told her husband, as she recorded in A Woman of Egypt. “Egypt will not be a democracy until women are as free as men.”

The attempts of some liberal clerics to defend the limited legal amendments supported by Jehan were undermined by the growing influence of Wahhabi Saudi Arabia. Despite the backlash from conservative Muslims, in the summer of 1979 her husband granted her wish and issued decrees improving the divorce status of women, as well as a second law that set aside 30 seats in parliament for women. These measures, which were later passed through parliament, became known as “Jehan’s laws”.

She was born Jehan Raouf in Cairo, into an upper-middle-class family, the third child of Safwat Raouf, an Egyptian surgeon, and his wife, Gladys Cotrell, a British music teacher, who had met in Sheffield when Safwat was studying medicine at the university. Jehan was raised as a Muslim, according to her father’s wishes, but she also attended a Christian secondary school for girls in Cairo.

She met Anwar at a summer party at her cousin’s house, not long after he was released from prison for the second time for his revolutionary activities; he was also recently divorced. The idealistic Jehan was impressed, despite her mother’s initial misgivings and the 15-year age gap. They married the following year, and went on to have four children.

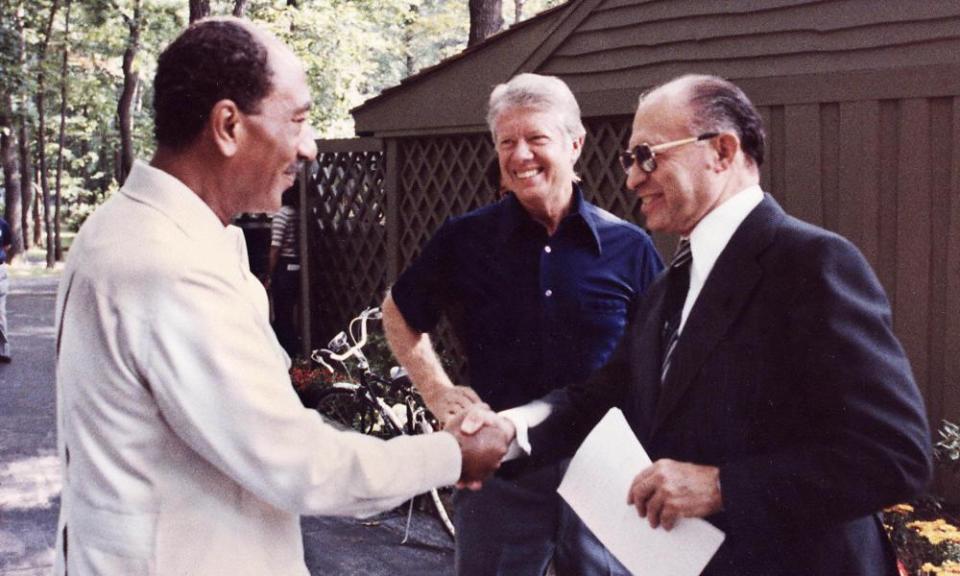

In 1977 Anwar flew to Jerusalem to propose a peace settlement to the Israeli Knesset, and the following year he signed the Camp David accords, the first peace treaty between an Arab nation and Israel, with the prime minister Menachem Begin and the US president Jimmy Carter. Jehan, who was a far more visible first lady than President Nasser’s wife had been, later made a point of saying that she had stood by her husband even though the peace agreement was highly controversial in Egypt.

I knew that he would be killed, she told the BBC

While he had believed that the affection of the armed forces for him was such that they could not be infiltrated by militant Islamists, she later told the BBC: “I knew that he would be killed.” She begged him to wear a bullet-proof vest but he refused, and was proud of the new uniform that he had had designed for a military march-past on the outskirts of Cairo.

When people were looking up at the Egyptian air force planes flying in formation and doing aerobatics, Jehan noticed an army truck pulling out of the line of artillery vehicles and stopping in front of the reviewing stands. Then she saw soldiers with machine-guns running towards the stands. Her husband stood up, was riddled with bullets, and fell. The glass through which she and her grandchildren were watching was likewise splintered by bullets, and her bodyguard pushed her to the ground.

Jehan spoke of the shock of losing the man who was not only “my beloved husband whom I loved all my life, but ... my partner”.

Her aspiration to higher education had eventually been realised, with a BA (1977) in Arabic literature and an MA (1980) in comparative literature at Cairo University, and she followed these with a PhD (1986). In later years she was a visiting professor at several US universities, and continued to promote international peace and women’s rights. A second book, My Hope for Peace, followed in 2009.

She is survived by her three daughters, Lubna, Noha and Jehan, her son, Gamal, and 11 grandchildren.

• Jehan Sadat, women’s rights campaigner, human rights activist and writer, born 29 August 1933; died 9 July 2021

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance