Jamie Dimon’s 7% rates may come even without the Fed's help

What these headlines miss is the fact that a lot of tightening has already happened since policymakers last raised rates in July

The Federal Reserve’s hawks have been back on the speaking circuit,and markets are abuzz that rates may have to move higher than previously expected. Someone apparently just took out a big short position premised on the chances that rates markets underestimate the odds of an increase in November. And, of course, JPMorgan Chase & Co Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon has warned clients to prepare for a worst-case scenario of a move in the direction of 7%.

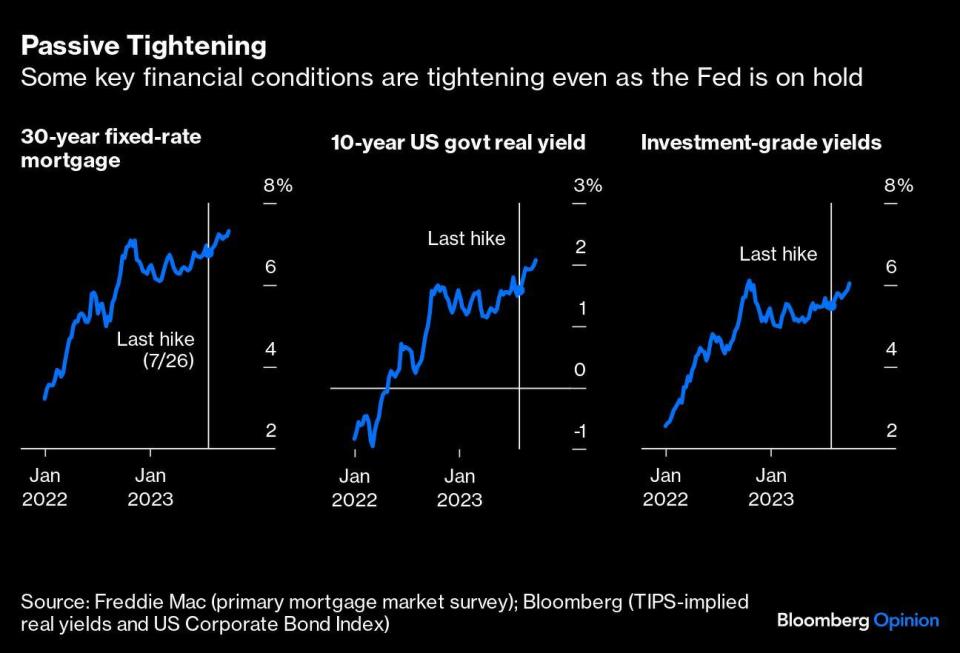

What these headlines miss is the fact that a lot of tightening has already happened since policymakers last raised rates in July.

There are many ways to measure financial conditions — and they don’t all agree— but it’s hard to look at the surge in real rates, investment-grade corporate yields and mortgages and not believe that conditions have grown significantly more restrictive in recent months. On a real basis, government yields have surged 70 basis points since the Fed’s last rate increase in July and are near the highest since January 2009. The average for a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage has climbed to 7.31% from 6.78% in July and is now the highest since 2000. And the all-in yield on an investment-grade corporate bond is back within a whisker of its 13-year high.

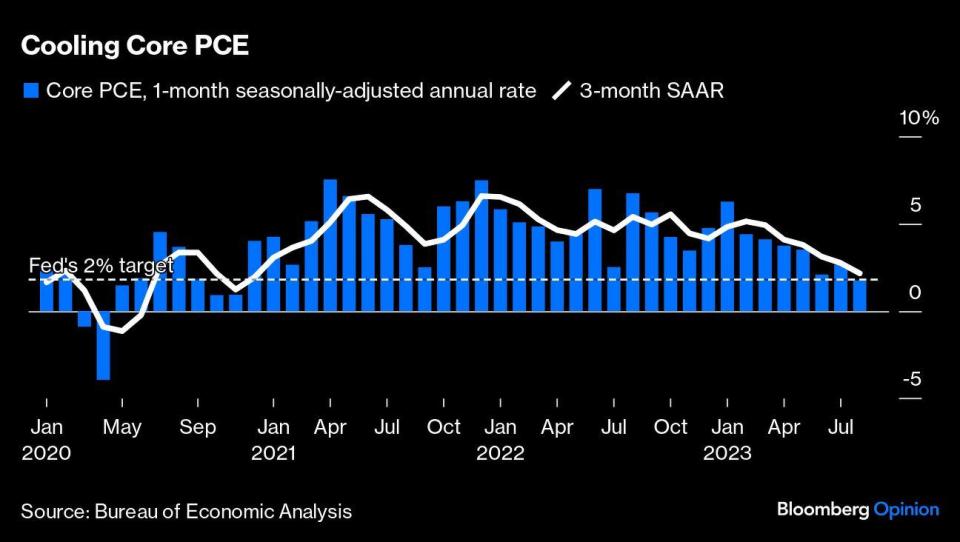

Next, there’s the effective tightening that’s happening simply from the drop in inflation. The appropriate level for nominal interest rates is always, in part, a function of inflation itself, which has been cooling (energy prices notwithstanding). According to the Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections, the median policymaker thought this month that a fed funds rate of 5.6% would be appropriate in the context of expected core personal consumption expenditure inflation of around 3.7% for the fourth quarter. But a report Friday showed that core PCE advanced just 0.1% in August from a month earlier after two consecutive monthly increases of about 0.2%. On a three-month annualized basis, that leaves the metric at 2.2% — remarkably close to the Fed’s 2% target.

Put another way, the Fed’s inflation projections may well be too high, which means their rate outlook may be as well. Here’s how Omair Sharif, president of Inflation Insights LLC, described the math in a note on Friday:

If we average 0.2% on the core PCE from September to December, then the Q4/Q4 reading will be 3.34%

If we average 0.25% on the core, then Q4/Q4 will be 3.49%.

You’d need to average just over 0.3% to hit the Fed’s 3.7% projection for Q4/Q4. So, unless you have a sustained reacceleration penciled in for the core PCE, it’ll be tough to see the Fed hit their estimates.

Doubtless, there are risks to this thesis. Some may worry that the disinflationary help from used cars and other durable goods may be tapped out, putting the onus on other categories. Others may worry that surging energy prices — which aren’t directly a part of core PCE — may bleed into the index through increased transportation costs, for instance. But clearly, the current trend is encouraging.

The argument for higher rates now essentially tends to revolve around the observation that growth has been strong, which it certainly has been. Revisions published on Thursday put second-quarter annualized GDP growth at 2.1% — slightly above many estimates of the economy’s potential. That has suggested to many economists that the Fed isn’t putting sufficient restraint on the economy to bring demand into alignment with supply and achieve the goal of bringing inflation all the way back to 2%.

But it’s important to remember how unique the current inflation fight has been — and, specifically, how quickly the supply side of the equation has been adjusting. Austan Goolsbee, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago president who is seen as a dove on the rate-setting committee, made a compelling presentation on Thursday precisely on the risks of indexing policy to that “traditionalist” view of how the world has worked in the past. Based on historical relationships between rate increases and the economy, Chicago Fed analysis suggests that the US should have already fallen into recession (which it hasn’t, setting aside the quirky contractionary quarters in 2022) and core PCE shouldn’t begin falling into mid-2024 (which it already has).

Clearly, this time around has been unique. Here’s Goolsbee (emphasis mine):

First, GDP fell more quickly than the typical policy tightening effect. While the level at this moment is close to its average response, the typical pattern has further steep declines coming. Second, employment has been much stronger than expected, so it would need to weaken a lot to follow the typical relationship. Third, inflation fell much sooner than the historical average. And if past correlations were to hold, most of the reduction in inflation from monetary policy actions to date is still to come, and it would be large.

And here’s how he sums up the findings:

... something very different is going on: Either nonmonetary shocks are heavily influencing the economy or the nature of the monetary policy environment we are working in today is different. I believe both of these factors are at play. If so, we need to be extra careful about indexing policy to this traditional view of what the incoming data on output and the labor market mean for the inflation outlook.

Goolsbee is clearly among the most dovish among voters on the Federal Open Market Committee, so not everyone is likely to heed his warning, but I’m heartened to know that he’s a voice at the table. Policymakers must bear in mind all of the de facto tightening that has already occurred in the economy since July; the additional effects that may yet be in the pipeline; and the simple fact that we’re in relatively uncharted policy territory. The Fed will get another round of inflation and labor market data before it announces its next decision on Nov. 1. But ultimately, the available information suggests they should continue to wait cautiously and see how far positive supply-chain developments and this recent bout of passive tightening will carry them.

See Also:

Click here to stay updated with the Latest Business & Investment News in Singapore

The Fed has rained on the parade, but investing locally retains its positives

Get in-depth insights from our expert contributors, and dive into financial and economic trends