'The ultimate insult': How U.S.-listed Chinese companies are gaming American investors

As scrutiny over unfair Chinese business practices intensifies amid drawn out U.S.-China trade discussions, investors are debating another contentious issue: minority American shareholders “squeezed out” by U.S.-listed Chinese companies.

The companies all follow the same playbook: After tapping into U.S. capital through a public listing, management turns around and takes the company private at a significantly cheaper valuation. That same management then relists the company back home in China, at a much higher valuation, leaving executives with a big windfall — and average retail investors with the biggest losses.

“They’re just trying to squeeze every last drop of blood out of U.S. shareholders and then go on and relist and do a new IPO in Chinese markets for three times or five times the transaction price in the U.S,” Peter Halesworth, manager for Heng Ren Partners, who has invested in some of these companies and wrote a white paper on the privatization trend, told Yahoo Finance. “It’s the ultimate insult at the end of the process.”

More than 60 U.S.-listed Chinese companies have gone private since 2013.

"While it's 'America First' when it comes to trade with China, Americans' rights are not the priority in the stock markets,” Halesworth said. “Here foreign issuers have unusual privileges, and many Chinese companies have abused these privileges and disadvantaged and damaged American shareholders' wealth and retirement funds."

Consider internet security firm Qihoo 360 Technology. In July 2016, the company announced a privatization offer that valued shares held by U.S. investors at $77, reflecting a valuation of $9.3 billion. Two years later, it relisted on the Shanghai Stock Exchange for a $62 billion valuation, a return of more than 550%.

Medical Device company Mindray Medical listed on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange three years after going private at $3.3 billion in the U.S., a significant discount to its IPO valuation. Its market cap in China within three months? More than $22 billion.

In December 2015, Wuxi PharmaTech was taken private at an equity value of $3.3 billion. The company has since relisted as 2 separate entities — one in Hong Kong and one in Shanghai — with a combined market cap of $21.6 billion.

Wuxi and Qihoo both now face separate class action lawsuits filed by U.S. investors, claiming the companies provided misleading statements to undervalue the companies.

Minority shareholders

Corporations have done that, in part by exploiting a cross-border legal loophole. While the companies are listed in the U.S., they are classified as Foreign Private Insurers (FPIs), subject to regulation by their home country’s exchange. FPIs are also exempt from corporate governance practices by which most publicly listed domestic firms must comply, including a requirement to host annual shareholder meetings.

Further complicating the issue is the controlling share structure of the companies, which allows founders to retain voting control. Minority investors, who own less than a 50% stake in the company, have little say in the direction of the company and are left powerless to contest a low-ball buyout offer. While that itself is not unique to Chinese firms, they have largely escaped shareholder repercussions because they are domiciled in the Cayman Islands, where minority investors have less protection than in Delaware, where most U.S. companies are registered, according to Harvard Law Professor Jesse Fried.

“The problem from the perspective of minority shareholders is the fact that all the defendants, the assets, the records, are all in the People’s Republic of China, which makes them unavailable,” Fried says. “It also drives up the cost of litigation.”

Class-action lawsuits

Still, investors are fighting back.

Just last month, U.S. shareholders for Wuxi PharmaTech filed a class action lawsuit seeking damages in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. The plaintiffs allege company executives violated federal securities laws, when they issued “false and misleading statements” aimed to undervalue the company and lied about its intentions to spinoff the company’s assets and relist shares in China.

Tony Heaver-Wren, a partner at offshore law firm Appleby, says minority shareholders have successfully found recourse by using a provision in the Cayman Islands’ legal code that entitles them to seek appraisals and claim the fair value of their holdings. One case, which involves China’s Shanda Games and Hong Kong hedge fund Maso Capital Investments, led to a payout to shareholders that was 80% higher than the initial price accepted, according to the Wall Street Journal. Maso has now appealed that ruling to a top U.K. court, seeking a higher premium, a decision that Heaver-Wren says will likely have wide implications for similar cases that are pending.

But Heaver-Wren says an overwhelming majority of the disputes have ended in settlement. Out of 25 lawsuits that have been filed in Cayman courts, only four have gone to trial.

“The reality is that these companies capitulate. They don’t believe in their story so much that they see it through and win,” Heaver-Wren says, adding that dissenting shareholders have won every case that has gone to trial, with the Court ruling that fair value payout be higher than that advocated by the company.

‘The environment of the trade war is encouraging this‘

The political winds may be shifting too. Last December, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board issued a joint statement, that singled China out for limiting the access of U.S. regulators, investigating the financial reporting of companies traded on U.S. exchanges. Since then, Congressman Mike Conaway (R - TX, 11th District) has introduced a bill that would delist for three years any U.S.-traded Chinese companies that don’t disclose their auditors. Senator Marco Rubio (R - FLA) has publicly pushed for more scrutiny as well.

“I think, in part, the environment of the trade war is encouraging this,” says Paul Gillis, a professor at Peking University, who testified before Congress last month. “I have also learned that these things just seem to take a long time to gain traction.”

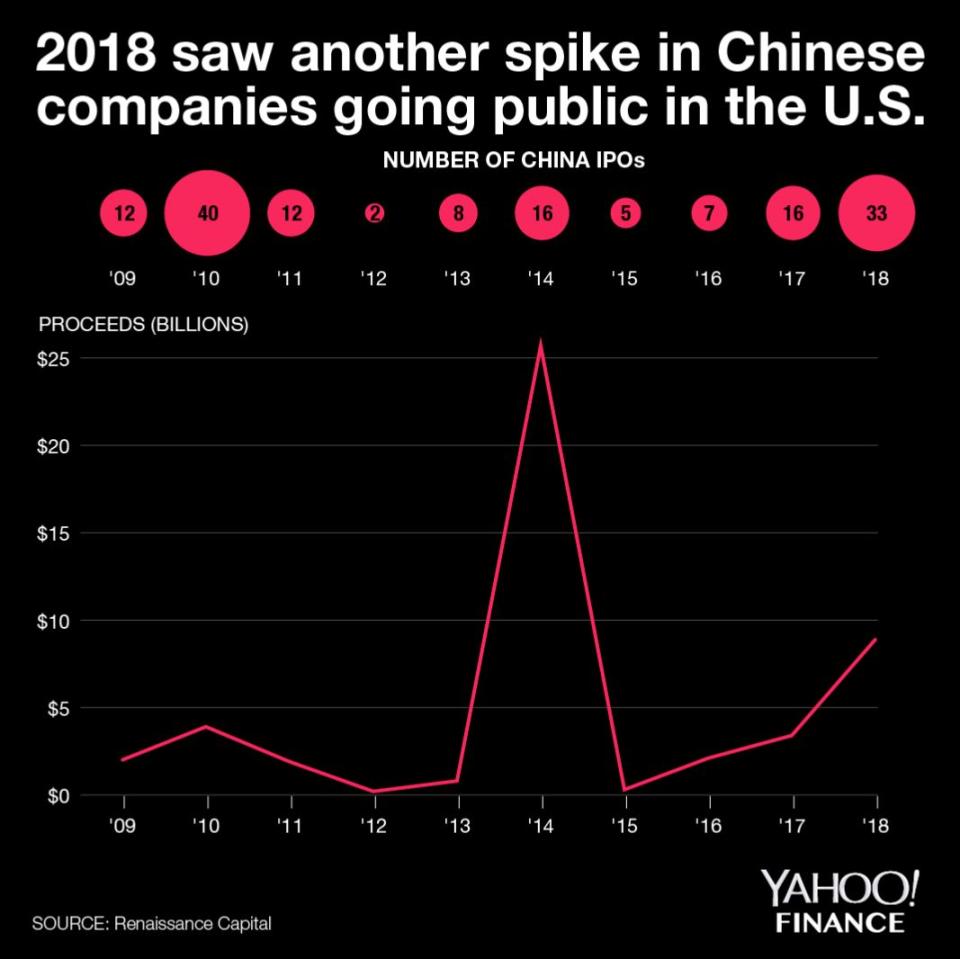

The pressure has yet to deter Chinese companies from listing on American exchanges. Thirty-three went public in the U.S. last year — double the number from the previous year. And in 2018, Chinese companies accounted for 17% of all U.S. IPOs.

NOTE: A version of this story was first published on March 18, 2019.

—

Akiko Fujita is an anchor and reporter for Yahoo Finance. Follow her on Twitter at @AkikoFujita

More from Akiko:

'Really bad business practice': U.S. security experts sound off on Huawei

U.S.-China showdown: Huawei has 'completely taken over' the Mobile World Congress

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance