Fracking pioneer Aubrey McClendon 'may have been running a Ponzi scheme, but he believed'

Listen on Apple Podcasts

Part 3 of Yahoo Finance’s Illegal Tender podcast about the life and death of Aubrey McClendon. Listen to the series here.

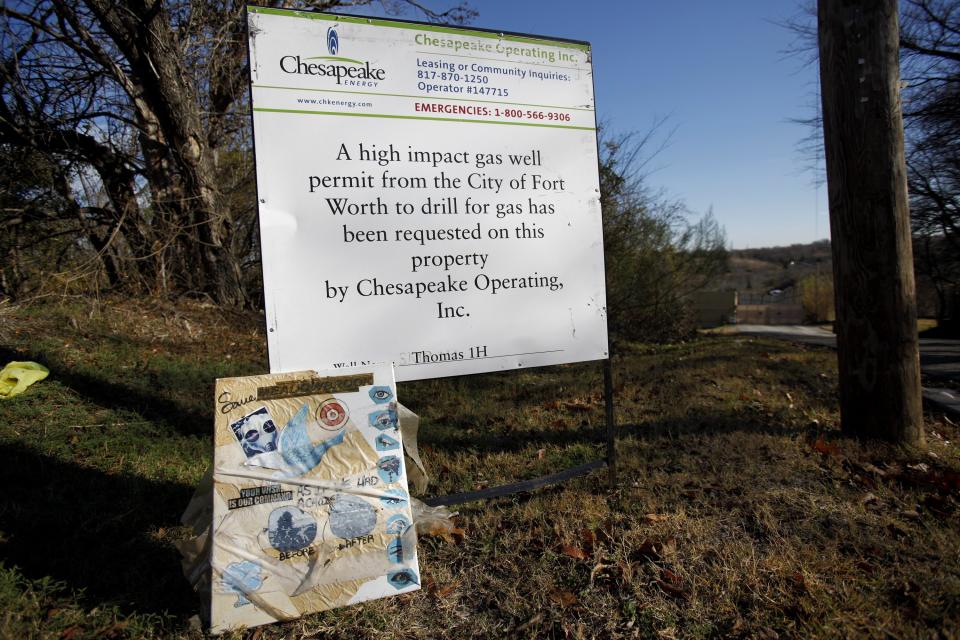

On May 1, 2016, the Justice Department charged former Chesapeake Energy CEO Aubrey McClendon with violating antitrust laws. It sent out a press release, which is still on the DOJ website: "Former CEO indicted for masterminding conspiracy not to compete for oil and natural gas leases."

The next day, McClendon died in a car crash.

According to the Justice Department, McClendon had been conspiring for years with another company to rig bids for the purchase of oil and natural gas leases in Northwestern Oklahoma in order to suppress prices.

Illegal Tender by Yahoo Finance is a podcast that goes inside mysteries in the business world. Listen to all of season one: Aubrey McClendon's life, death and fallen empire

The winning bidder would then give an interest in leases to another company, and they'd do business together and co-own the leases. This is what the public heard in the days following McClendon's death. The timing strongly implied a conclusion that it was a suicide by a disgraced businessman who had decided to opt out of whatever the criminal charges would bring.

According to people who knew McClendon, he loved to drive around way over the speed limit without a seatbelt and was known to use his phone while behind the wheel. Most people who knew him – friends, investors, rivals – saw him as a man who was impossible to faze, giving equal weight to the theory that it was just an accident, even if the circumstances suggested death by suicide. As the police in Oklahoma City said, no one may know for sure.

“He may have been running a Ponzi scheme, but he believed,” Bethany McLean, who wrote a book about McClendon and his business, told Yahoo Finance. “And he's unlike these other characters we see in that you meet plenty of business people with insane ideas who are willing to risk every penny of somebody else's money in order to execute their idea.”

No free cash flow

The end of McClendon’s life was also the end of an era for the fracking industry.

McClendon’s role in American energy policy is significant. Thanks to Chesapeake, the idea of energy independence has changed dramatically. Whether it’s right or wrong — some people like Charlie Munger of Berkshire Hathaway argue the U.S. ought to use up other nations’ energy first — McClendon proved that there is a lot of oil and gas underground in the U.S.

Illegal Tender by Yahoo Finance is a podcast that goes inside mysteries in the business world. Listen to all of season one: Aubrey McClendon's life, death and fallen empire

Unfortunately, he also showed that it’s hard to square the basic math. If it costs $100 to get a barrel of oil out of the ground, or the equivalent amount of gas, but you can only sell it for $60, you simply won’t be able to make a profit or create free cash flow. While some individual wells have been known to do that, the industry by and large is waiting for the money to come in.

To wit, there have been numerous short-sellers hoping to make money off this fundamental issue. Because wells are finished so quickly, one must drill and drill to keep going, always finding new land. So far, there are many fracking companies still out there doing well. But new doubts are starting to form as to whether they will ever pay off.

Illegal Tender by Yahoo Finance is a podcast that goes inside mysteries in the business world. Listen to all of season one: Aubrey McClendons life, death and fallen empire

Transcript below:

Ethan Wolff-Mann: 00:01 On May 1st, 2016 the Justice Department charged former Chesapeake Energy CEO Aubrey McClendon with violating antitrust laws. It sent out a press release, which is still on the DOJ website. "Former CEO indicted for masterminding conspiracy not to compete for oil and natural gas leases." The next day he was dead.

According to the DOJ, McClendon had been conspiring for years with another company to rig bids for the purchase of oil and natural gas leases in Northwestern Oklahoma in order to suppress prices. The winning bidder would then give an interest in leases to the other company, and they'd do business together and co-own the leases. This is what the public heard in the days following McClendon's death. The timing strongly implied a conclusion, that it was a suicide by disgraced businessman who had decided to opt out of whatever the criminal charges would bring.

But it wasn't that simple. As the police chief said at the time, "We may never know 100% what happened." However, we do know some stuff. From Yahoo Finance, this is the last episode of Illegal Tender season one. I'm Ethan Wolff-Mann.

So what exactly was Aubrey McClendon accused of and how did it all go down?

Bethany McLean: 01:22 Chesapeake and McClendon are basically colluding with other companies to keep the price of acreage they're going to acquire or lease down by agreeing, together, as to what price they'll pay. The government starts digging into these allegations. Chesapeake itself settles the charges using this very little known program called the Conditional Leniency Program in which Chesapeake gets shielded, Chesapeake itself, the company gets shielded from any further issues with criminal antitrust laws. But in order to be admitted to this program, Chesapeake has to say, "Someone did something. There was a criminal violation here." So in order to get admitted to the program and shield itself, they have to blame somebody else, and they blame McClendon. They say he's the one who did it.

There's an email that Aubrey McClendon sends an executive of another company and it reads this this way: "Should we throw in 50/50 together here, rather than trying to bash each other's brains out on lease buying?" This becomes a key piece of evidence that the government has. But the great irony here is that McClendon is the guy with the reputation for always overpaying, right? The fact that he would be taken down by the government on charges of trying to keep prices artificially low, when he was a guy who never seemed to care if he paid an artificially high price, is really ironic.

EWM: 02:42 This point is why a lot of people were surprised. On the one hand Aubrey and his original business partner, Tom Ward started Chesapeake after competing with each other. But on the other, Aubrey McClendon was also this guy with a wild reputation for overpaying for literally everything, which Marc Rowland, the former Chesapeake CFO, remembers very well and still defends.

Marc Rowland: 03:06 We were out of our minds, we were crazy, blah, blah, blah. But if you ran the math, the little bit of acreage dollars didn't matter at all compared to the wealth that you were accumulating by having the rights for the oil and gas. But, you're right, he bragged about that regularly, and so the lessors loved to see Aubrey coming. It was the reverse of what the government was saying. They were detracting from the economic value. He was adding to it.

EWM: 03:34 To some people in the oil and gas industry, like Rowland, Aubrey's actions sounded like a common practice, something that a lot of people and companies did with joint ventures.

MR: 03:44 It was done by every oil and gas company and every executive every day, and it has been done in the history of the business. This was the first and only time that this has been brought up. You go back to the basis of the industry in the offshore days, all of those leases out there were taken by multiple parties because the risks were so great that nobody wanted to own 100%, and this is just a variation of that.

EWM: 04:12 As Aubrey is under investigation, and he knows it, he keeps frantically raising money with his new company, American Energy Partners. The pressure was enormous, but it's sort of hard to imagine that he didn't think he was going to be able to handle whatever would come based on how DP was going.

BM: 04:28 He'd guaranteed so much of the money he'd raised with personal guarantees. That actually ratcheted up the pressure enormously because those guarantees allowed him to be sued personally if he was accused of any kind of criminal activity. So, literally, he had everything at stake.

EWM: 04:45 Besides the potential everybody-does-it aspect of Aubrey's alleged crimes, that would have probably ameliorated any sort of feelings of shame, there's a few other compelling reasons for thinking that his death was an accident. Aubrey was probably one of the most risk-loving figures in business history. He himself was all in multiple times, and he had lost it all before. Again, this is the guy who was chiller than the pilot as a plane was going down, literally, as Rowland told us in a previous episode.

BM: 05:15 I mean, there wasn't a single penny more he could have risked than what he did. What's funny is even through this, can you imagine this? Your empire is crumbling. You're struggling to raise the money you need to keep your empire going. You're facing, not only possibly going to jail, but losing every penny you've ever made and facing losses for the rest of your life. And he seems perfectly unfazed according to people who know him. A guy I know took him to a basketball game in the spring of 2016 as all of this is just coming to a head, this unbelievable amount of pressure. This guy says, "Even with his world crumbling around him, he was ever a promoter and ever optimistic."

EWM: 05:53 This is the main reason that people like Bethany and Marc think Aubrey's was an accident, but the timing is tough to square.

BM: 06:01 It's 5:30 PM on March 1st of 2016, and a federal grand jury indicted him for a conspiracy to rig bids. The person on the other side isn't identified, but it's Tom Ward, McClendon's former partner. That night, McClendon was supposed to be at a private dinner with some very influential potential business partners, including Vicente Fox , the former president of Mexico. McClendon never shows up. The guests open some of his bottles of wine from his legendary collection because this was always McClendon's thing. When he would throw these dinners, he would always bring these incredibly exclusive bottles of wine, and he would always open them and share them with people because he wasn't a collector who hoarded his wine. He bought it in order to share it and to open it and to throw these just dinner parties that were extraordinarily fabulous.

Anyway, so the indictment becomes public the next morning, and there's a statement from McClendon. "The charge that has been filed against me today is wrong and unprecedented. Anybody who knows me, my business record in the industry in which I have worked for 35 years, knows that I could not be guilty of violating antitrust laws. I will fight to prove my innocence."

Right around the same time, John Raymond's firm, which is the major backer of Aubrey's new empire, sends a letter to its investors informing them that they are going to cease any and all new business activities with McClendon. So he's really... he's done. Around 9:00 AM, he leaves his office to meet somebody for breakfast at Pops, which is this restaurant he owns. That's part of McClendon's grand effort to redevelop Oklahoma city. According to later police reports, he's traveling in a Chevy Tahoe almost 90 miles an hour, well over the speed limit of 50 miles an hour, and his car collides with this concrete wall supporting a highway overpass at 9:12 AM, and the Tahoe bursts into flames.

There's a series of 911 calls describing the scene. "It looks like a Tahoe, and it looks pretty rough. The cab is completely crushed. The vehicle just exploded." There's speculation after this because the captain of the Oklahoma City Police, Captain Paco Balderrama, tells reporters that McClendon basically just drove through this grassy area right before colliding with the embankment. He says, "There was plenty of opportunity for him to correct and get back on the roadway and that didn't occur."

So most people think it was a suicide. But, in the end, the police couldn't find any evidence that he was seeking to end his own life. There's no suicide note. There are no despondent calls to other people. There's no sign that this guy was down and would have done such a thing. A few months later, the state medical examiner rules that his death was an accident.

EWM: 08:48 What do you think?

BM: 08:50 You can never know. The coincidence is such that it's to believe it wasn't a suicide. It's just hard to believe. At the same time, this was a guy who was like Icarus with nine lives, right? Had crashed, and then had come back and had crashed and had come back. So why wouldn't he have believed that he might've been able to find a way out? So I don't think I'll ever be sure one way or the other.

EWM: 09:18 Now Marc Rowland has another pretty compelling reason that this was an accident.

MR: 09:23 I've been on that road a zillion times with Aubrey going out to his farm. It's a very treacherous small, two-lane road that narrows into a one lane to go under a railroad pass with concrete abutments on either side. Here's three things I'd point out. Aubrey drove the fastest of any person that I've ever known on the city streets and highways. He came up to my father's funeral in Wichita, Kansas in 2000, and he got the highest speeding ticket that was ever awarded in Kansas. He was going a hundred and something through a construction zone, a $5,000 penalty or something like that. He drove like that all the time.

MR: 10:07 Second thing is, is that he hated seat belts, and when he got a new car he would have the seatbelt warning disconnected. So him not wearing a seatbelt, he never wore seatbelt. The third thing is, is that he multitasked to everybody's chagrin all the time. It wasn't uncommon for him to have two or three cell phones on him. He could have easily dropped one. I'm sure he was under a lot of stress, so it's quite feasible to me that he could have had a heart attack. He was 56 or seven, I forget exactly, but somewhere in that age, and he had lived a stressful life, self-induced a lot of times, but he loved that farm out there. So II just don't think, I mean, he had dinner with his daughter and her newborn the night before and been talking to her. I said, "Was your dad okay?" She said, "He was just like Dad." I don't believe he killed himself, but nobody will ever know.

EWM: 11:08 It's hard to know how to view Aubrey after all this. Is he a scammer? Is he a believer? Is he just somebody who was right but at the wrong time. Is he sympathetic, or is he a villain? Bethany has some thoughts.

BM: 11:21 I have never really thought of Aubrey McClendon as a fraud. He may have been running a Ponzi scheme, but he believed. And he's unlike these other characters we see in that you meet plenty of business people with insane ideas who are willing to risk every penny of somebody else's money in order to execute their idea. What you don't see as often is the person who is willing to risk every penny of somebody else's money, but also every penny of their own. I mean, Aubrey went bankrupt, essentially, three times and died bankrupt because he had put his own personal guarantee behind so much of the money he raised for what was essentially his third go-around, maybe even fourth. You could count it that way. This guy believed.

People would tell me stories about how at industry conferences, Aubrey would be speaking, and the rooms with ExxonMobil and other giant companies would basically be empty because everybody would be flooding in to hear what Aubrey had to say. I mean, he occupied that kind of position in the industry. But it's funny, because of his death, it's harder to get a clear view of Aubrey than it otherwise would've been.

EWM: 12:33 What was Aubrey's lasting legacy? There were a couple ones. Driving the industry into fracking, but even further, perhaps ushering in a gas boom. Before Aubrey and fracking, we thought we were running out of gas as a country.

BM: 12:46 There were these hand-wringing hearings in Congress. I think even Alan Greenspan, then the chairman of the Federal Reserve, worried about what the United States was going to look like as we were facing this impending shortage of natural gas. So fracking just could not have changed the picture more dramatically. There wasn't any push to use more natural gas because we didn't think we had any.

EWM: 13:06 Now we live with cheap gas because we have this massive supply due to fracking, and it's changed oil as well. Up until 2015, the industry wasn't even allowed to export oil on the global market.

BM: 13:19 One of the great ironies was this ban against oil exports that had been in place since the dark days of the 1970s, when we first began to fear our dependence on scary spots around the world, namely the Middle East, and feel like this stuff is so precious, we can't let any of it leave our shores. This ban on oil exports persisted for four decades, through every administration. Presidents, Republican and Democratic, didn't change it.

It changes in late 2015, and it's president Barack Obama, ironically enough, who ends the ban on exports. He signs it into law as part of the year-end omnibus spending bill. The industry is so quiet at this point because fracking is collapsing, and nobody's really thinking about it and it's not in the headlines anymore. As a result, the lobbyist who worked on the bill said that basically there was nothing. This thing that he had dedicated so much of his life to getting passed was kind of slipped into this spending bill, passes the House, passes the Senate, Obama signs it, everybody leaves town. He says he's just left there alone thinking that this momentous thing has happened. So he takes himself out for a steak in Manhattan by himself because there's nobody even left in town to celebrate with. It's funny because it's this incredibly momentous event, and yet it just slid by. I'm not sure, most people even realize that it happened.

EWM: 14:36 This is an interesting change, and it's one that some people think could cause problems. Though countless US presidents have sought US energy independence, there's some arguments to think that it's not necessarily the best strategy.

BM: 14:48 It's like, "How great it would be if we just could produce all of the energy we need to consume." But it's a totally flawed idea, which we can come back to. Why would you not use other people's supply of energy? why would you not be trying to save your own in case there's a day of need? But we as a country have never been all that good about thinking about and planning for the future.

EWM: 15:11 So what about the future for fracking? Well, it still does not look great financially speaking.

MR: 15:17 There's not a big profit margin in these wells. I've been in hundreds now, maybe close to a thousand wells in my IOG funding. We always focus on return on investment. I see the industry not really doing that. Many of these plays don't generate much more than a one-to-one or 1.1-to-one return on investment. That's why you're seeing the pushback, I think, from the investment community, saying, "Look, you're really not making any money. You've got a high velocity of cash going out and back in, but there's no real return on your equity."

EWM: 15:54 In the end, for guys like Rowland who have seen the industry try its utmost to make fracking work, it comes back to one thing, prices.

MR: 16:03 It's not going to work without higher prices in the gas area for sure. We need higher prices. Gas prices at 2.40 or whatever they are today at NYMEX, and then typically 80 cents to a $1.20 behind that at the wellhead. It's just inadequate to pay for the technology that's necessary.

EWM: 16:23 Rowland says that although the industry probably has figured out how to keep costs from running away in times of high prices and giddiness in the market, that probably still won't fix this price issue. Frackers, it seems, are looking for one of two Hail Mary's. The first, maybe prices go up somehow and allow them to get closer to breaking even by boosting up the revenue side. The second, maybe some wild technology can come along and save them to keep costs down, bringing that side of the equation under control. But no [inaudible 00:16:54] or any magic tech seems to be around the corner.

MR: 16:58 It's really hard to imagine what that technology could be. We have been innovators and have developed enormous technology advances. Wells that used to take 40 days when we first started drilling, or 60 days even, are down to being drilled in seven or nine days. But we've hit peak efficiency there. You can't even connect pipe any faster than that. I can't imagine what it is on the drilling side.

We're still dealing with rock that's incredibly dense and microdarcys of permeability and without massive quantities of [inaudible 00:17:38] and water, fluid, I don't know what you could do to fracture, stimulate the zone to where it would actually flow oil and gas. Marginal improvements, yeah, but you're talking about something that you've already said doesn't exist. It's really hard for me to imagine how you could overcome just the natural physical limitations of what you're doing 10, 12, 15,000 feet under the ground.

EWM: 18:09 Since her book came out, Bethany's taken an even more pessimistic view about whether fracking is going to work financially, which has probably been aided by all the articles from the Journal and others reporting a series of unfulfilled promises from the industry. It's almost like the subjects telling the emperor he isn't wearing any clothes.

BM: 18:30 I've become more of a skeptic than I was when my book came out. When my book came out, I would have said probably 60/40 no, but I wasn't convinced. I had a hard time taking a firm line for two reasons. One is that everybody who's tried to predict the history of energy or the future of fracking has been wrong, and they've usually been wrong by underestimating it.

EWM: 18:51 If this doesn't work out, it is not going to be good.

BM: 18:55 To me, the biggest question is, if the industry had to live on the cashflow it produces and has to end, what is essentially a Ponzi scheme, which is raising fresh money in order to finance production. If the industry can only reinvest its own profits, what's the real level of production? How much oil and gas can we actually produce? That, to me, is a really important question.

Even private equity investors, people who had put their money into this, one of them, one prominent guy said to me that if companies had had to live within cashflow, if they hadn't been able to keep raising these immense gobs of capital from outsiders, that the shale revolution would have grown at a quarter to half the clip that it actually did. That's the big question to me. I guess you could even ask the question one level deeper. Can these companies even produce free cashflow? Can they be profitable? Does the business work at all, even if it's shrinking?

EWM: 19:47 What would happen if that money spigot were to be turned off, if investors gave up and the cheap money ends?

BM: 19:53 It would not leave very many companies left at all, unless there's some sort of underlying transformation in their business model. But it would be very difficult for most of the industry to survive if rates were a lot higher and they could no longer raise fresh capital. I think you have a much, much smaller American shale industry.

EWM: 20:10 You said that you've been to Texas a few times to look at all of these things. What does a fracked well look like?

BM: 20:18 It's not really all that dramatic. It's actually kind of boring. It's just a lot of equipment, I mean, an immense amount of equipment. When you fly into Midland, all you see for miles everywhere are windmills and oil rigs.

EWM: 20:32 Besides the industry, there really is a lot at stake for all of this, not just for the industry, but for Americans and American businesses. Though we have made some very important steps towards a green future, so many people still rely on hydrocarbons to live and to work.

BM: 20:49 What's indisputable is that American fracking, the shale revolution, has changed the price that you pay at the pump. Almost more importantly though is the economic transformation that's come about as a result of fracking. If it weren't for fracking, the economy would have been substantially weaker in past years than it has been. Fracking has been this almost unheralded part of economic resurgence in the post-financial crisis landscape.

There are stories from North Dakota where the Bakken is, from the Permian, of places renting for thousands of dollars a month and people without many other skills making hundreds of thousands of dollars. These pockets of the country have seen this incredible economic resurgence as a result of fracking. There have been many bad things that have gone along with that as well, an increase in crime, an increase in use of natural resources. So it's not an unalloyed good thing, but it has provided a huge economic boost to those areas.

But then there are other ways in which fracking transforms our economy in ways that are less obvious. For instance, there's this whole talk now that Pennsylvania is going to become the new land of plastics. I always think of The Graduate when I hear this, "One word: plastics," but that Pennsylvania is going to turn into a plastics hub. That's in large part because all of the fracked gas coming from an area known as the Marcellus Shale, that suddenly you're going to have manufacturing of plastics, of things that can be made out of natural gas on American soil, which wouldn't have been here were it not for fracking.

EWM: 22:20 Some people think they know the future, and some of them have made very expensive bets on both sides about what will happen in all of this. While one side will doubtless end up right and vindicated, either the short-sellers or the believers, the craziest thing for me is that one person literally had the power to change the entire narrative. This is the most amazing thing about the McClendon story: one charismatic guy who got so caught up in it, he had this outsized effect.

Bethany and I came back to the old myths a few times while recording all this. The industry with its failure to recognize that it has this enormous problem, that it just can't make any money, is like the emperor's new clothes. But McClendon himself is this Icarus-like character, caught up in the giddiness of it all, and ever going towards the sun, which will eventually be his undoing, melting his wax and sending him crashing down to Earth.

BM: 23:16 I think that's interesting because oftentimes when we look at these stories of business gone wrong or business with bad endings, we think, "Well, the reason was greed. This executive was just out to make money for himself." But it's really clear in Aubrey's case that that wasn't it at all. His wife had plenty of money. He could have lived a lovely life being married to an heiress. If his motives were greed, there were plenty of opportunities along the way where he could have extracted hundreds of millions of dollars for his own benefit, and he never did. Instead, he continued to risk every penny he had and then some in an effort to build something. So there's something doomed but admirable about that in the end. The thing I love and admire about Aubrey McClendon is that it wasn't OPM. It wasn't other people's money. It was his own money.

EWM: 24:04 Illegal Tender is made by Yahoo Finance at our studios in New York City. This episode was written and hosted by me, Ethan Wolff-Mann. This episode was mixed and edited by Dan Brantigan, who also contributed music. Illegal Tender is produced by Alex Sugg. Thank you to Bethany McLean for being a key contributor to this story. To learn more about Aubrey's story, get her book, Saudi America, wherever good books are sold. And if you enjoyed this podcast, head over to Apple podcasts and leave us a five star rating and review it for the show. Until next time, thank you for listening to Illegal Tender.

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance