Self-repairing material plucks carbon from the air

It's borrowing a cue from plants.

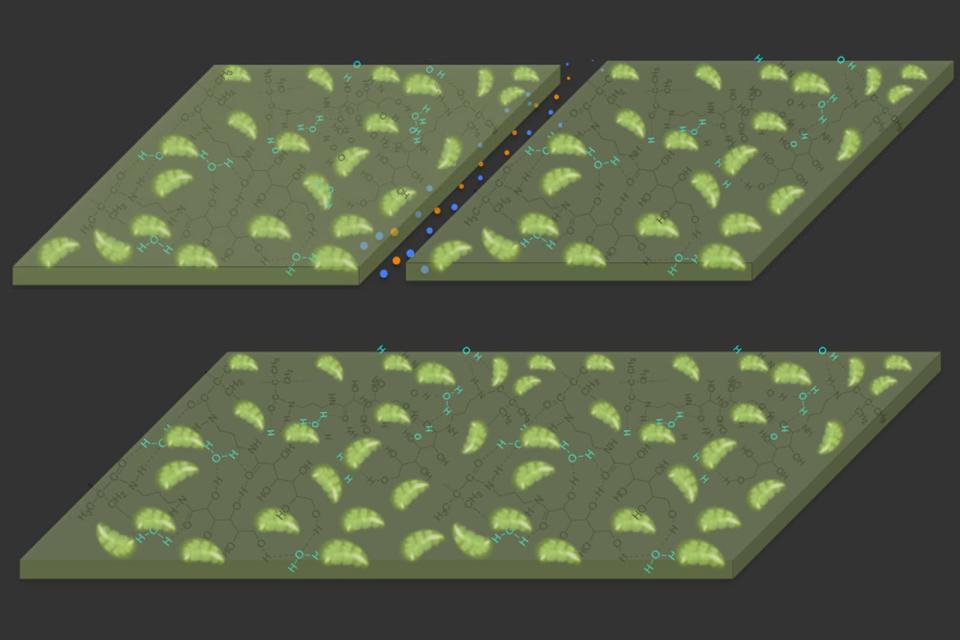

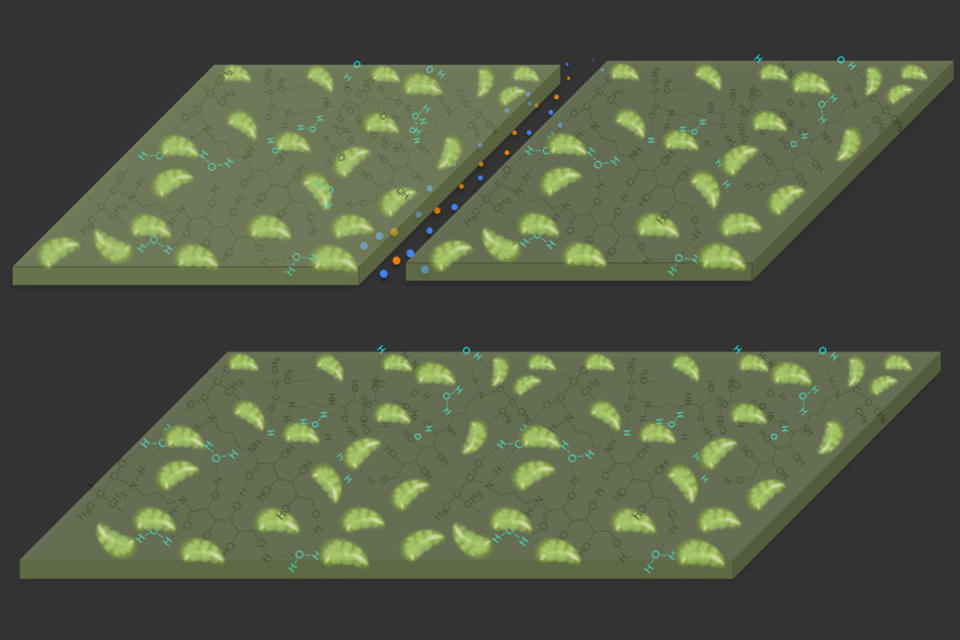

Scientists might have a particularly clever way to help the environment: they've developed a material that can not only heal itself, but could reduce CO2 levels in the process. The substance uses its combination of a gel-like polymer with chloroplasts (cell elements that handle photosynthesis in plants) to grow by snatching carbon from the air after exposure to light. If you cracked or scratched an already-solidified piece of this material, the newly exposed sides would promptly expand and fill the gap without requiring heat, ultraviolet light or other special reactions like you see with existing self-healing products.

Researchers have isolated chloroplasts before this, but these organic components tend to stop working a few hours after removal from a plant. The team made them more practical by significantly extending their useful lifespan.

There's more work to be done, such as replacing the chloroplasts with artificial catalysts that could achieve a similar effect. The potential applications are already clear, however. You could use the polymer as a building material that fixes itself while countering excessive CO2 emissions. It might function as a coating for other products, too. And it could even be economical -- construction crews could ship the material in liquid form and make panels out of it at the building site. Urban sprawl would still be a problem after this, but it might have its upsides for the planet.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance